TL:DR; Yet again Apple’s ban on third-party browser engines weakens security rather than strengthens it.

Researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Ruhr University Bochum have published papers describing two attacks dubbed SLAP and FLOP that impact Apple’s latest chipsets.

These attacks share conceptual similarities with the Spectre exploits, which affected most pre-2019 processors by exploiting speculative execution. While Spectre targeted branch prediction, SLAP and FLOP exploit load address and value prediction in Apple's latest chips.

For SLAP, Apple requested an extended embargo beyond the typical 90-day window, and the researchers ultimately waited 250 days before publishing. For FLOP, the researchers notified Apple 148 days prior to publication. In both cases, Apple has not provided any timeline for implementing mitigations to the researchers or the public.

SLAP

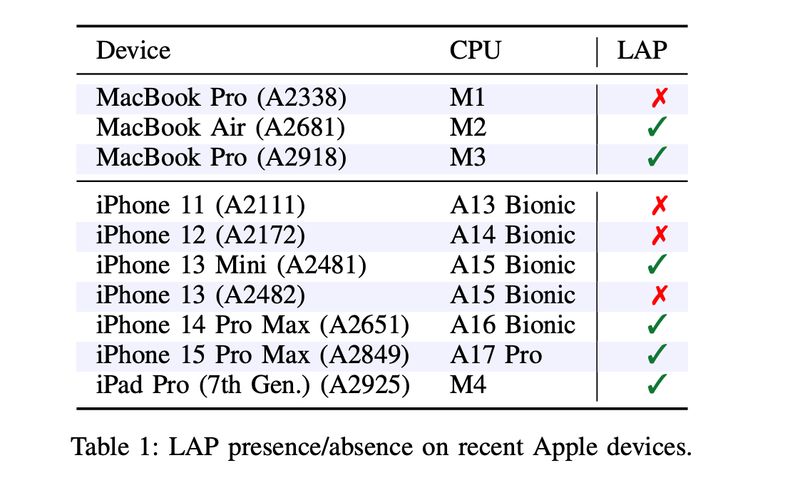

The SLAP attack targets Apple-designed processors, such as the M2, A15, and newer models that have a Load Address Predictor (LAP), which predicts the memory addresses of subsequent load instructions to optimize performance.

According to the paper, visiting a malicious website could potentially allow an attacker to access data from another arbitrary page on a different domain.

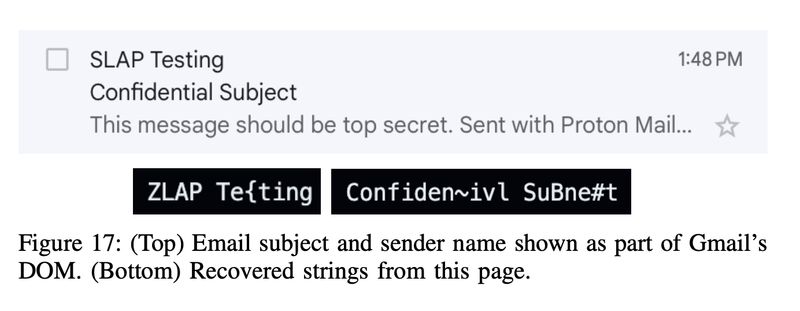

In their example in the paper, confidential email subject lines from Gmail can be accessed through a third-party website.

"We assume the target is authenticated to Gmail, and visits the attacker webpage. The attacker webpage allocates 1.7 MB of filler and training strings, and then calls window.open on Gmail’s inbox page when the mouse cursor is placed over itself. As Gmail loads, JavaScript in the page starts rendering the inbox, whose content is personalized to the target. Over repeated trials, we show that the subject line and the sender’s identity can land in the reachable out-of-bounds region of the LAP, allowing for recovery by the adversary in Figure 17." SLAP: Data Speculation Attacks via Load Address Prediction on Apple Silicon

This attack only works in Safari (and all browsers on iOS due to Apple's browser engine ban) running on devices with newer Apple-designed processors, such as the M2 and A15.

This attack does not work on other major browsers such as Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Opera, and Vivaldi on platforms where they can use their own browser engines.

This is due to a feature called site isolation which separates each domain into its own process, preventing malicious websites from accessing or stealing information from other sites.

"We emphasize the importance of site isolation [55], a mechanism preventing webpages of different domains from sharing rendering processes. Site isolation is already present in Chrome and Firefox [42, 55], preventing sensitive information from other webpages from being allocated in the attacker’s address space. While its implementation is an ongoing effort by Apple [3, 4], site isolation is not currently on production releases of Safari." SLAP: Data Speculation Attacks via Load Address Prediction on Apple Silicon

The researchers indicated that they disclosed the vulnerability to Apple on 24th of May 2024 (250 days prior to publication) under responsible disclosure:

“The researchers disclosed their findings to Apple on May 24, 2024. Apple’s Product Security Team acknowledged the report and proof-of-concept code, requesting an extended embargo beyond the typical 90-day window. At the time of writing, Apple has not shared a schedule regarding mitigation plans concerning the results presented in this paper.” SLAP: Data Speculation Attacks via Load Address Prediction on Apple Silicon

All browsers on iOS devices are affected by this exploit due to Apple's policy requiring all browsers to use the WebKit engine, effectively making them Safari under the hood. This means iOS users cannot switch to alternative browsers that might not be affected by SLAP.

FLOP

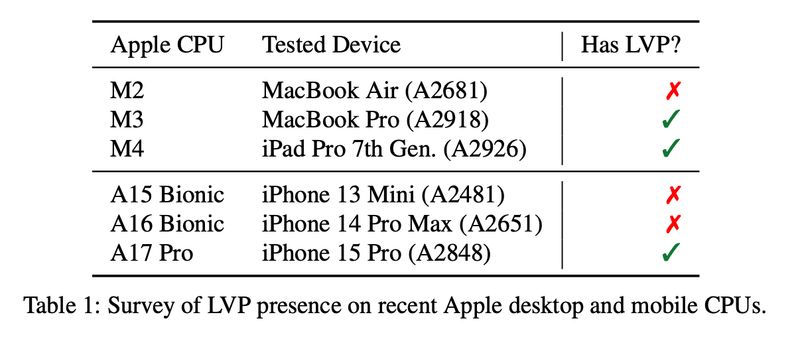

The FLOP (False Load Output Prediction) attack exploits a different aspect of speculative execution in Apple's M3+ processors. Specifically, it targets the Load Value Predictor (LVP), which predicts the outcome of data dependencies to improve performance. If the LVP predicts incorrectly, it can lead to the execution of instructions using incorrect data, potentially allowing an attacker to access sensitive information.

Unlike SLAP, FLOP affects all browsers. However, due to site isolation in browsers like Chrome and Firefox, the attack is limited to working between subdomains of the same site, rather than between completely unrelated websites. This does not entirely defeat the exploit but it does make FLOP significantly less concerning than SLAP on browsers other than Safari.

In Safari, an attacker could potentially gain access to data from any arbitrary website through a malicious site on an affected device. For example, data could potentially be accessed from gmail.com via exploit code running on attacker.com. On other browsers (using either Gecko or Blink) it would only be able to potentially gain access to data on other subdomains for example from attacker.example.com to target.example.com. This greatly limits the attack's scope.

Again, all browsers on iOS are impacted by this exploit, as users cannot take advantage of other browser engines' superior protections due to Apple’s browser engine ban.

Responsible Disclosure. We disclosed our results to Apple’s Product Security Team on September 3, 2024 upon completing the initial version of the writeup. Apple has acknowledged our writeup, and after an internal investigation, communicated that they plan to address this in an upcoming security update without sharing further details. FLOP: Breaking the Apple M3 CPU via False Load Output Predictions

The researchers disclosed this vulnerability to Apple on September 3, 2024 (148 days before publication) but did not notify Google or other browser vendors, possibly viewing the threat as minor due to existing mitigations in those browsers, meaning such notification was not necessary or warranted.

Site Isolation

Site isolation was introduced in Blink (Chrome, Opera, Vivaldi, Brave) in July 2018 as a security feature to mitigate Spectre-style attacks, and Edge since 2020. It was added to Gecko (Firefox) in December 2021 with Project Fission. It is still being implemented for Firefox Android.

Full site isolation requires additional memory to keep different domains in separate processes. As a result, all browsers make trade-offs and do not enforce full site isolation in every scenario. For example, Chrome disables site isolation on devices with less than 2GB of RAM and, on Android devices, primarily applies it to sites where it can detect that the user is logged in.

While Safari has some level of process isolation, it lacks full site isolation and does not as aggressively keep processes separate between different domains as other browsers. As a result Apple lags several years behind in this important protection and has prevented any rival from bringing this security feature to iOS via its browser engine ban.

Impacted Chips

What's the Takeaway?

On affected devices, Safari users should be aware that malicious websites could potentially steal data from other domains. On macOS, users can switch to alternative browsers while waiting for Apple to implement site isolation or similar protections.

Apple has repeatedly claimed that allowing other browser engines onto iOS will weaken security for iOS users. Apple claims that its unilateral control over the only browser engine on iOS allows it to minimize the patch gap for all browsers on iOS and thus improve security.

Apple recalls that the WebKit requirement provides a high base level of stability, security, and privacy that is more effective than Android for a variety of reasons, including because it does not result in a ‘patch gap’ which in turn gives rise to 'significant security risks'. Apple’s response to CMA provisional decision report

In this case, not only has Apple failed to patch SLAP on iOS, despite having 250 days advanced notice, but they have also blocked all other vendors from doing so.

On iOS, changing browsers offers no protection from this exploit since all browsers must use the same WebKit engine. At the same time, this shields Apple from losing market share, as no tech professional or tech website will recommend switching browsers on iOS in this case, given that all browsers on iOS are essentially Safari under the hood. As a result, competitive pressure to quickly address vulnerabilities is eliminated. Competition and the fear of losing market share are powerful forces for improving security, but for browsers on iOS, they have been entirely nullified.

This highlights yet again how Apple’s ban on third-party browser engines weakens security rather than strengthens it.