As 2025 begins, it's a perfect moment to reflect on 2024’s developments, achievements, and what lies ahead regarding regulators, browsers, and web applications.

Last year was incredibly busy, and together with you, we have made real tangible progress toward a more competitive browser and Web App ecosystem.

If there’s one key takeaway from 2024, it’s this: advocacy works. When those who love what makes the web amazing come together, we can achieve wonders!

Share and join the conversation: X/Twitter, Mastodon, LinkedIn and Bluesky.

Who is Open Web Advocacy?

If you’re new to Open Web Advocacy (OWA) we are a non-profit organization committed to pushing greater competition within the browser and Web App ecosystems. Our objectives are:

- Ensuring fair and effective competition for browsers across all operating systems.

- Enabling Web Apps to compete fairly and effectively with native apps, in particular by advocating for feature parity with native apps where technically feasible.

Our primary focus is to ensure what made the web great on desktop, happens for mobile. Users should be able to access web apps and websites freely, without the excessive control, fees, and restrictive interfaces imposed by gatekeepers. This vision for the future is one that drastically decreases the cost of development and increases the pace of innovation while enhancing functionality, security and privacy for everyone.

Imagine, a future where developers and businesses can write their software once, deploy to any device without the gatekeepers… this is a future worth fighting for.

What did OWA do in 2024?

Last year we worked extensively with multiple regulators, and our allies around the world towards our common goals. The core of our focus was in the EU with the implementation of the Digital Markets Act and the UK with the Browsers and Cloud Gaming Market Investigation Reference. Additionally, we participated in several technology and regulatory conferences to explain the critical issues that need to be addressed and how the web can fundamentally change the software industry if it was allowed to compete fairly.

In particular these three 2024 papers are worth a read for those interested in browser and Web App competition:

You can also see Alex Moore talk at Web Directions - Code 24.

Stuart Langridge talk at State of the Browser:

Bruce Lawson (who is continuing the fight for a fairer web at Vivaldi) at FrontMania:

John Ozbay talking at the European Commission's Apple DMA Workshop:

We were also delighted to join the JS Party podcast to chat to Amal Hussein and the Igalia Chats podcast with Brian Kardell and Eric Meyer.

At times it can seem that work in the regulatory space is slow, but together with the developer community, critical advocacy from allies, and excellent work by key regulators we achieved some significant victories and tangible progress in 2024.

Saving Web Apps

Out of all the things we achieved this year, the absolute biggest was saving mobile Web Apps and we couldn't have done it without the enormous support of the developer community and the hard work of the EU commission.

So what happened and why was this victory so critical in protecting the Web App ecosystem?

On 28th of January 2024, Apple broke all Web Apps in the EU in the iOS 17.4 beta, by converting all Web Apps to simply bookmarks which would then open in a browser tab ensuring that all local data would be lost, notifications would no longer work and the Web App would no longer work as a separate app.

Initially, they tried to keep it a secret. Extraordinarily, there was no mention of this in their DMA compliance plan, the iOS beta notes or the Safari beta notes. Given how detailed these typically are and the magnitude of the change, it is impossible that this was an oversight. Clearly Apple was attempting to sneak this past the developers, users and regulators to provide everyone minimal time to respond.

Over the next two weeks, Apple’s silence was deafening. No reply was given to a Safari/WebKit ticket, Apple developer forums, twitter discussions, and no statement was provided to the many journalists seeking comment.

After 2 weeks, in the face of steadily increasing developer and media backlash, Apple was forced to rush out a statement where they confirmed they were deliberately breaking Web Apps and that it had been planned:

To comply with the Digital Markets Act, Apple has done an enormous amount of engineering work to add new functionality and capabilities for developers and users in the European Union – including more than 600 new APls and a wide range of developer tools.

The iOS system has traditionally provided support for Home Screen web apps by building directly on WebKit and its security architecture. That integration means Home Screen web apps are managed to align with the security and privacy model for native apps on iOS, including isolation of storage and enforcement of system prompts to access privacy impacting capabilities on a per-site basis.

Without this type of isolation and enforcement, malicious web apps could read data from other web apps and recapture their permissions to gain access to a user’s camera, microphone or location without a user’s consent. Browsers also could install web apps on the system without a user’s awareness and consent. Addressing the complex security and privacy concerns associated with web apps using alternative browser engines would require building an entirely new integration architecture that does not currently exist in iOS and was not practical to undertake given the other demands of the DMA and the very low user adoption of Home Screen web apps. And so, to comply with the DMA’s requirements, we had to remove the Home Screen web apps feature in the EU.*

EU users will be able to continue accessing websites directly from their Home Screen through a bookmark with minimal impact to their functionality. We expect this change to affect a small number of users. Still, we regret any impact this change — that was made as part of the work to comply with the DMA — may have on developers of Home Screen web apps and our users. Apple

(Since Deleted)

OWA and others in the industry recognized that if this change were implemented, it would almost certainly spell the end of mobile web apps. With the EU being such a critical market and significant concerns that Apple might replicate the change in other regions, the move would effectively end any future investment in the sector.

We, of course, had to act. We immediately informed the DMA team and then launched a series of surveys to demonstrate how detrimental this would be to businesses and users in the EU. We had over a thousand responses in a few short days and this allowed us to hand the EU excellent information about the immediate cost of Apple breaking Web Apps.

We then worked shifts around the clock to launch our incredibly successful open letter to Tim Cook. The letter gained worldwide support support and has had 4264 individuals and 441 organisations sign. Signatures include two European MEPs (Karen Melchior & Patrick Breyer); a number of significant EU companies such as social media platform Mastodon; and individuals (advocating in their personal capacity) who work for SwissLife, Tchibo, W3C, Mozilla, Google, Microsoft, Vivaldi, BBC, Financial Times, Red Hat, Oracle, Amazon, Wikimedia, Vercel, Netlify, Shopify, Spotify, AirBNB, Berlin University of the Arts, Open State Foundation - Netherlands, Cloudflare, Meta, Chase, Squarespace, Reddit, Atlassian, Maersk, Paypal, Salesforce, block, Adobe, ebay, Zynga, booking.com and thoughtworks; and many other developers and organisations from over 100 countries.

On the 1st of March 2024, Apple cancelled its plans to break Web Apps in the EU, issuing a statement:

UPDATE: Previously, Apple announced plans to remove the Home Screen web apps capability in the EU as part of our efforts to comply with the DMA. The need to remove the capability was informed by the complex security and privacy concerns associated with web apps to support alternative browser engines that would require building a new integration architecture that does not currently exist in iOS and iPadOS.

We have received requests to continue to offer support for Home Screen web apps in iOS and iPadOS, therefore we will continue to offer the existing Home Screen web apps capability in the EU. This support means Home Screen web apps continue to be built directly on WebKit and its security architecture, and align with the security and privacy model for native apps on iOS and iPadOS.

Developers and users who may have been impacted by the removal of Home Screen web apps in the beta release of iOS and iPadOS in the EU can expect the return of the existing functionality for Home Screen web apps with the availability of iOS 17.4 and and iPadOS 17.4 in early March. Apple

We would like to say a massive thank you to the DMA team as Apple's decision is no doubt related to the investigation they had opened and our most heartfelt thanks to the thousands of developers and individuals who took the time to fill in our survey and sign the open letter. We are grateful for your help and no doubt will need it again. Know that your voices were heard and made a difference.

Successfully pushed Apple to remove its problematic line about dual engine browsers

For 16 years, Apple has enforced a ban on third-party browser engines, limiting competition in the browser market. Now that this ban has been lifted in the EU, browser vendors must be allowed to gradually roll out their own engines through phased implementation and multi-variant testing. Deploying a new engine on an unfamiliar operating system is a complex task, requiring careful, incremental progress to identify bugs and performance issues.

As a result, it is essential that all browser vendors be allowed to ship dual engine browsers. That is, browsers that can use both the system provided WKWebView and their own engine within a single binary. However, Apple had added a rule in their contract to explicitly ban this:

Be a separate binary from any Application that uses the system-provided web browser engine; Apple Browser Engine Entitlement Contract - 2024-06-24

This restriction lacks clear or reasonable justification and appears to conflict with the DMA, which allows API restrictions only when they are justified on strictly necessary and proportionate security grounds.

On October the 23rd, the contract was updated to remove that single line. Apple also announced the change in this blog post:

Developers of apps that use alternative browser engines can now use WebKit in those same apps.

Apple - Blog on iOS 18.2

While this is a step forward, Apple still has other rules in place that make it difficult for browser vendors to port their own engine to iOS. For example, browser vendors are forced to ship it as a separate browser app for the EU, which means their users in the EU will not be automatically updated to the browser with its own engine. Browsers will then need to reacquire all of their existing users, asking them to switch to the EU-only version of the browser and uninstalling the existing one. This is a confusing and high friction process for users.

This will also need to be fixed to make it viable for browser vendors to ship their browsers in the EU. There are three main ways that Apple can fix this:

Allow browser vendors to use their own engine globally.

Allow browser vendors to ship a different binary in the EU under the same bundle id.

Provide a system flag to allow the browser vendor to know if we are allowed to use these APIs and their own engine. The browser will then use the APIs and their own engine in the EU but then use the WKWebView exclusively outside the EU. Apple also has the technical ability to block access to these APIs outside the EU.

Without implementing one of these solutions, the burden on browser vendors will remain excessively high, undermining competition in the browser market in the EU. We are of the opinion that no browser vendor will be willing to ship with this problem unresolved.

Got Apple to let browser vendors test their own browsers

Astonishingly, Apple decided earlier this year to make it impossible for browser vendors to test their own browsers (that wished to use their own engine) if the developers were not physically located in the EU.

The Register has learned from those involved in the browser trade that Apple has limited the development and testing of third-party browser engines to devices physically located in the EU. That requirement adds an additional barrier to anyone planning to develop and support a browser with an alternative engine in the EU.

It effectively geofences the development team. Browser-makers whose dev teams are located in the US will only be able to work on simulators. While some testing can be done in a simulator, there's no substitute for testing on device – which means developers will have to work within Apple's prescribed geographical boundary.

Thomas Claburn - The Register

This was clearly ridiculous. We had extensively covered and pushed for this issue to be resolved, and since the release of iOS 18.2, Apple now allows not only browser vendors, but all app developers (wherever they are in the world), to test their own apps which use APIs or functionality that Apple currently reserves for itself outside the EU.

However, there is still no solution proposed by Apple to allow web developers outside the EU to test and maintain their websites and Web Apps for EU consumers on third-party browsers which use their own engine. This is and will remain a significant barrier to browser competition on iOS.

Our proposal is that web developers outside the EU should be able to download test-versions of EU browsers via an Apple Developer Account for the purpose of testing their own products.

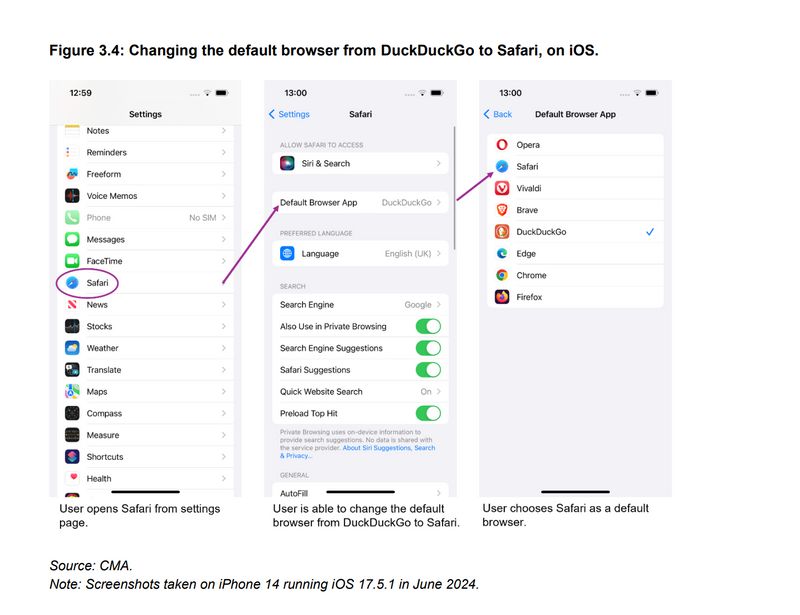

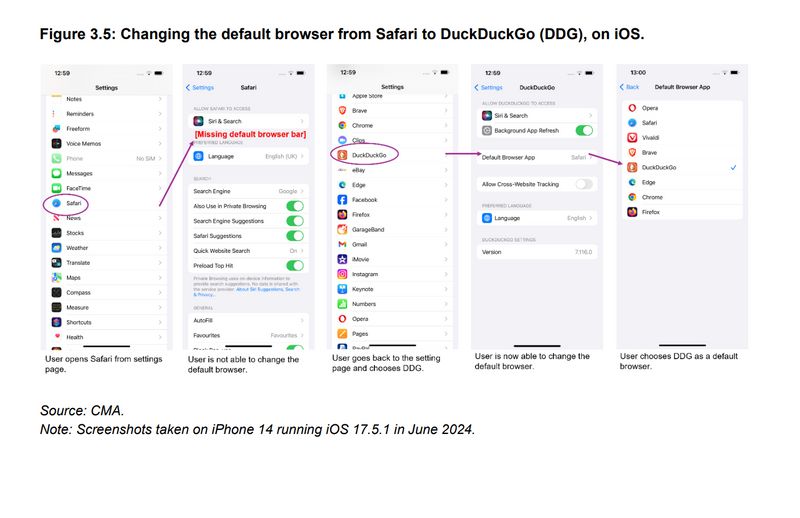

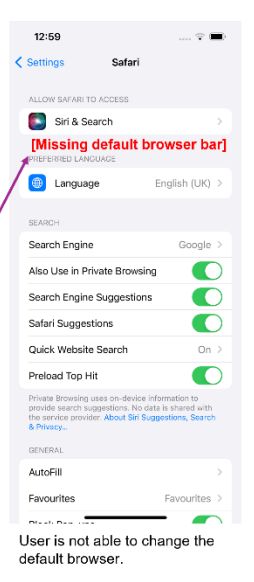

Made Apple fix their trick of hiding the Default Browser Option if Safari was the Default

Earlier this year we reported on a deceptive pattern that Apple had hard-coded into iOS, which made it harder for users to change their default browser if your current default browser was already Safari.

This was picked up by Ars Technica 2 weeks later and was subsequently fixed by Apple.

Bafflingly, Apple claimed our original report was false in their response to the UK’s regulator.

In response to our article discussing this, Apple stated that:

Apple told MacRumors that Open Web Advocacy's allegation that Apple is misleading the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is inaccurate. Apple says it told the CMA that the design of the identified browser setting was changed in a recent software update. The design was apparently never intended to discourage users from setting third-party browsers as the default.

Apple - Responding to MacRumours

Apple has declined to elaborate on what its purpose was (if it wasn’t to make it harder for users to switch browsers) and why they stated our initial report was false rather than that they had simply fixed the issue we had identified.

Secured Hotseat Placement on the EU Choice Screen

In August, Apple announced they would implement one of our recommendations that browsers chosen in the choice seat would get placed in the hotseat/dock/first homescreen replacing Safari.

If Safari is currently in the user’s Dock or on the first page of the Home Screen and the user selects a browser that is not currently installed on their device from the choice screen, the selected browser will replace the Safari icon in the user’s Dock or in the Home Screen

Apple - About the browser choice screen in the EU (2024-08-19)

Previously, being selected as the default browser did not grant the hotseat. This means it is entirely possible, and in fact likely, that many existing users who have set a third party browser as their default browser will still have Safari or Chrome on certain versions of Android in the hotseat.

Only about half (52%) of people understand that their default browser is opened when they, for example, click on a link in an email or document.

[..]

over half (53%) also erroneously believed that their default browser would automatically be pinned to their task-bar.

Mozilla – “Can browser choice screens be effective?” paper

Changes like this will not push the needle overnight, so what does success look like?

There are two forms of success in choice architecture. One is removing behaviour that is blatantly unfair or manipulative. The removal of the behaviour is a success in its own right, regardless of any outcome.

The second is in allowing space for new and smaller browser vendors to thrive. Even the most perfect choice screen will not wildly change user preference over night. The biggest names in browsers are the ones that will be picked the most and the browser of the operating system will still have a significant advantage. What choice screens need to do to succeed, is inform the user that they have a choice and create an opening for third-party browser vendors to get a foothold.

If third-party browsers managed to gain an additional 10% of the total market share on iOS or Android, that would be a resounding success.

Anti-Competitive Issues to be Fixed

There are still a vast amount of issues to fix here, and we will continue to work with regulators around the world until all these issues are fixed globally. A non-exhaustive list of the issues we are aiming to fix is below.

Apple

- Allow browser vendors to keep their existing EU consumers when switching to use their own engine.

- Allowing web developers to be able to test their web software on third-party browsers using their own engines outside the EU

- Restricting Apple's API contract for browsers down to strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures.

- Make clear what the security measures are for third party browsers using their own engine by publishing them in a single up-to-date document.

- Implementing Install Prompts in iOS Safari for Web Apps.

- Allowing Browsers using their own engine to install and manage Web Apps.

- Removing any App Store rule that would prevent third party browsers from competing fairly.

- Make Safari uninstallable.

- Make notarization a fast and automatic process, as on macOS.

- Allow direct browser installation independently from Apple’s app store.

- Allow users to switch to different distribution methods of a native app and allow developers to promote that option to the user.

- Respect the user's choice of default browser in SFSafariViewController.

- Don’t lock Safari to Apple Pay

- Don't break third party browsers for EU residents who are travelling.

- Opt-Into Rights contract should be removed.

- Core Technology Fee should be removed.

- Publish a new more detailed compliance plan.

- Share WebAPK Minting with third-party browser vendors subject to strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures.

- Respect the user's choice of default browser in the Android Google Search App and the Google App.

- Make Chrome uninstallable on Android.

Microsoft

- Remove edge-links and instead respect the user's choice of default browser in various Microsoft apps.

- Remove and permanently disable various popups, banners in Windows, Bing and Edge that aim to discourage users from switching browser.

- Allow filetype defaults for browsers to be changed more easily.

- Allow users to switch browser in S-Mode, subject to strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures.

Meta

ByteDance

The Regulatory Landscape at the end of 2024

The EU

In the EU, the landmark Digital Markets Act came into force on 7th March 2024.

It contained 3 incredibly important passages for browsers and Web Apps.

First, prohibiting browser engines is banned:

Article 5(7) The gatekeeper shall not require end users to use, or business users to use, to offer, or to interoperate with, an identification service, a web browser engine or a payment service, or technical services that support the provision of payment services, such as payment systems for in-app purchases, of that gatekeeper in the context of services provided by the business users using that gatekeeper’s core platform services.

Digital Markets Act - Article 5(7)

(emphasis added)

Second, the DMA explicitly states why gatekeepers can not ban third-party browser engines: Gatekeepers should not be able to dictate the functionality of Web Apps:

When gatekeepers operate and impose web browser engines, they are in a position to determine the functionality and standards that will apply not only to their own web browsers, but also to competing web browsers and, in turn, to web software applications. Gatekeepers should therefore not use their position to require their dependent business users to use any of the services provided together with, or in support of, core platform services by the gatekeeper itself as part of the provision of services or products by those business users.

Digital Markets Act - Recital 43

(emphasis added)

Third, gatekeepers must provide access to all the same APIs that are available to the gatekeepers own apps and services. This access may be subject to strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security conditions:

Article 6(7) The gatekeeper shall allow providers of services and providers of hardware, free of charge, effective interoperability with, and access for the purposes of interoperability to, the same hardware and software features accessed or controlled via the operating system or virtual assistant listed in the designation decision pursuant to Article 3(9) as are available to services or hardware provided by the gatekeeper. Furthermore, the gatekeeper shall allow business users and alternative providers of services provided together with, or in support of, core platform services, free of charge, effective interoperability with, and access for the purposes of interoperability to, the same operating system, hardware or software features, regardless of whether those features are part of the operating system, as are available to, or used by, that gatekeeper when providing such services.

The gatekeeper shall not be prevented from taking strictly necessary and proportionate measures to ensure that interoperability does not compromise the integrity of the operating system, virtual assistant, hardware or software features provided by the gatekeeper, provided that such measures are duly justified by the gatekeeper.

Digital Markets Act - Article 6(7)

(emphasis added)

Finally the DMA comes with real teeth. It grants the Commission the power to fine gatekeepers found not to be in compliance up to 10% of global revenue, which in Apple’s case would be up to $39 billion USD per offence.

The Commission has initiated three non-compliance proceedings against Apple, two against Google, and one against Meta. In its preliminary assessment, the Commission has determined that Apple is not compliant with DMA obligations related to steering. Additionally, two specification proceedings have been launched for Apple, a formal process through which the Commission can clarify specific steps required to ensure compliance with the DMA.

Apple

A proceeding has been opened into Apple's app store policies that may breach the DMA’s requirement to allow developers to “steer” consumers to external offers free of charge. Apple has been found preliminary in non-compliance in this proceeding.

A proceeding has been opened into Apple's new contractual requirements, including Apple’s “Core Technology Fee” for third-party developers and app stores that may fail to meet DMA compliance standards.

A third proceeding has been opened into Apple continuing to offer non-compliant terms within the EU as an option to developers, rather, having the DMA compliant terms be opt-in.

The Commission has opened a specification proceeding into Apple's interoperability request process. The proposed measures include increased upfront transparency of internal iOS and iPadOS features, timely communication and updates, fair and transparent handling of rejections and a more predictable timeline.

Finally the Commission has opened a specification proceeding to outline the proposed measures the Commission considers Apple should implement to effectively comply with its interoperability obligations in relation to several iOS connectivity features, predominantly used for and by connected devices. These can be notifications, automatic Wi-Fi connection, AirPlay, AirDrop, or automatic Bluetooth audio switching.

A proceeding has been opened into Alphabet’s app store policies that may breach the DMA’s requirement to allow developers to “steer” consumers to external offers free of charge.

A proceeding has been opened into Alphabet’s preferential treatment of its own vertical search services (e.g., Google Shopping and Google Hotels) over competitors.

Meta

- A proceeding has been opened into Meta for its recently introduced “pay or consent” model in the EU. The Commission is assessing whether this complies with the DMA’s requirement that gatekeepers secure user consent before combining or cross-using personal data.

However, despite the DMA being in force since March 2024, not a single browser vendor has been able to ship a browser using its own engine.

Two big barriers, not allowing browser vendors to test their own browsers outside the EU and preventing browser vendors from also using the WkWebView, have both been resolved.

The primary remaining barrier to this is Apple insisting that these browser vendors ship a new browser in the EU, rather than upgrade its existing one, forcing them to reacquire all their EU users from scratch.

Instead, transaction and overhead costs for developers will be higher, rather than lower, since they must develop a version of their apps for the EU and another for the rest of the world. On top of that, if and when they exercise the possibility to, for instance, incorporate their own browser engines into their browsers (they formerly worked on Apple's proprietary WebKit), they must submit a separate binary to Apple for its approval. What does that mean exactly? That developers must ship a new version of their app to its customers, and 'reacquire' them from zero.

Alba Ribera Martínez - Deputy Editor at Kluwer Competition Law Blog

(emphasis added)

USA

DOJ vs Google

The United States v. Google LLC is a federal antitrust case brought by the Department of Justice (DOJ) against Google that started on October 20th, 2020. The suit alleged that Google had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by illegally monopolizing the search engine market.

In August 2024, the DOJ won the suit when Judge Mehta ruled that Google held a monopoly on their search engine technology, and illegally used that position in securing Google's position with mobile device and website partners.

The DOJ has published a list of outlined potential remedies that they are seeking. The list is dense and the DOJ is considering a lot of different and overlapping remedies.

Of the over twenty five remedies that the DOJ are proposing, we are concerned by the significant potential harm to the Web from just two of the proposed remedies. They are: a total ban on revenue sharing with browser vendors in return for setting Google as the default search engine and a forced sale of Chrome by Google. These remedies strike at the heart of the web platform's funding model and will do unintended but severe damage.

This will be a major focus of OWA in 2025 due to its potential to severely undermine our goals and damage the open web. Our aim in relation to this case is to ensure that the DOJ addresses Google’s monopolistic practices effectively while safeguarding the web as a vital resource for billions of consumers and millions of businesses around the world. If your business relies on the web and are concerned about these two remedies please contact us.

The DOJ is expected to deliver their updated remedies on March 7th 2025 and a remedies trial is expected to be held in April.

You can hear us discuss these remedies on the Igalia Chats podcast with Brian Kardell and Eric Meyer.

DOJ vs Apple

In 2024 the Department of Justice (DOJ) launched a lawsuit against Apple arguing that they have illegally monopolized the US smartphone market. The government claimed Apple broke the law by maintaining a closed ecosystem for the iPhone in pursuit of profits and at the expense of consumers and innovation.

The essence of the DOJ case is that Apple has made iPhones worse for US consumers in order to increase lock-in, reduce interoperability and block competitors from competing. The DOJ also argues that Apple uses security and privacy as a shield to justify its anticompetitive conduct.

Apple wraps itself in a cloak of privacy, security, and consumer preferences to justify its anticompetitive conduct. Indeed, it spends billions on marketing and branding to promote the self-serving premise that only Apple can safeguard consumers’ privacy and security interests. Apple selectively compromises privacy and security interests when doing so is in Apple’s own financial interest

DOJ vs Apple

The DOJ has a number of examples of how Apple has done this, including discussing Apple's ban on third party browser engines and how lack of visibility for Web Apps on iOS makes them unviable.

Developers cannot avoid Apple’s control of app distribution and app creation by making web apps—apps created using standard programming languages for web-based content and available over the internet—as an alternative to native apps. Many iPhone users do not look for or know how to find web apps, causing web apps to constitute only a small fraction of app usage. Apple recognizes that web apps are not a good alternative to native apps for developers. As one Apple executive acknowledged, “[d]evelopers can’t make much money on the web.” Regardless, Apple can still control the functionality of web apps because Apple requires all web browsers on the iPhone to use WebKit, Apple’s browser engine—the key software components that third-party browsers use to display web content.

DOJ vs Apple

(emphasis added)

It is worth noting that one of the reasons that many users on iOS are unaware of how to install Web Apps is Apple has for years refused to implement install prompts and hidden away the mechanism for installing them on the share menu. At the same time, Apple has gone to great lengths to make it easy to link to and install Apple’s own iOS app store native apps from Safari.

This case is in its early stages and will likely run for several years.

The UK

DMCC

The Digital Markets, Competition, and Consumers Act 2024 came into effect on January the 1st 2025, granting the UK regulator authority to designate companies with Strategic Market Status (SMS).

This can be thought of as the UK’s equivalent to the EU’s Digital Markets Act, although it has differences in how it is implemented as covered in this article. The primary difference is that the DMCC is less proscriptive than the DMA and allows the CMA to impose bespoke conduct requirements on each SMS firm.

Firms with Strategic Market Status (SMS) designation will be required to adhere to one or more tailored conduct requirements (CRs). The DMCC Act provides a structured framework for the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to follow when implementing these requirements.

Non-compliance with a conduct requirement could result in substantial penalties, amounting to up to 10% of the company’s global turnover.

It will likely take till towards the end of the year (9 months from initiation) to designate the first batch of SMS companies.

CMA MIR Investigation

As readers may recall, the UK Competition and Markets Authority launched a Market Investigation Reference (MIR) into mobile browsers and cloud gaming on June 10th 2022.

From our extensive work in supporting the Mobile Ecosystems Study, we know the key reason the Market Investigation Reference into Browsers and Cloud Gaming was launched was to enable the free, open and interoperable ecosystem of the web to contest Apple’s and Google’s app stores, reducing costs for UK’s consumers and businesses. While regulators across the world were focused on app stores, the UK was the only regulator that was looking towards the web and web apps to solve these issues on mobile ecosystems. This aim was made clear by the opening statements of the Browsers and Cloud MIR:

We all rely on browsers to use the internet on our phones, and the engines that make them work have a huge bearing on what we can see and do. Right now, choice in this space is severely limited and that has real impacts – preventing innovation and reducing competition from web apps. We need to give innovative tech firms, many of which are ambitious start-ups, a fair chance to compete. Andrea Coscelli - Chief Executive of the UK's Competition and Markets Authority

(emphasis added)

When we last wrote about this investigation, we were concerned that the MIR might fail in its goal of allowing third party browsers to enable effective competition from Web Apps and that the focus on web apps had been lost.

Specifically we were concerned there was no remedy that would allow browsers to install and manage web apps using their own engine. That is Apple would be able to lock all browsers (including ones with their own engine) into using their current WebKit implementation of installed Web Apps.

We are delighted to say that the MIR team has listened to both us and all of the many many businesses and web developers who wrote in. A huge thank you to every developer and business that took the time to write in and explain their concerns, it really makes a difference!

For example, ‘equivalence of access’ would need to include enabling third-party browsers using alternative browser engines to install and manage PWAs (rather than relying on WebKit to support parts of this process), including enabling mobile browsers using alternative browser engines to implement installation prompts for PWAs. MIR - Provisional Decision Report

(emphasis added)

While a very crude measure, “web app” has gone from being mentioned 5 times in the remedies paper to 300 times in the provisional decision report.

The provisional decision report is exceptionally long but worth a read if you have time.

Overall we support the vast majority of the proposed remedies and believe that the MIR team have done an incredible job given the vast array of complex issues related to browsers and web apps that they have tackled. We do have a number of concerns that we will cover in more detail in future blog posts but which are contained in our full response paper and our remedies response paper for those who wish to read about them now.

In the provisional decision report, the MIR team has opted not to use the powers of the MIR but instead to hand over its findings to the CMA who will use the DMCC as the enforcement and oversight mechanism.

The MIR team has a statutory deadline of March 16th 2025 to publish their final report.

Japan

In 2024, Japan’s parliament passed into law a bill to promote fair competition on smartphone operating systems, similar to the EU’s Digital Markets Act and the UK’s Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill.

This bill was based on the Japan's Head Quarters for Digital Competition's Final Report which OWA consulted on. You can read our paper here.

The bill aims to promote fair and free competition on smartphones by preventing large tech companies from abusing their position as providers of platforms to block or advantage their own services.

Violators will face fines equivalent to 20% of the domestic revenue of the service that violated the law. The rate of the fine can be increased to 30% for repeated violations.

The final bill contains a number of interesting articles relevant to browsers and Web Apps:

- Banning browser engines is prohibited.

- Must share APIs and services of the operating system to the same level as the services used by the designated providers. Justifiable measures may be applied.

- Designated providers shall make it easy to change the default settings of the operating system.

- Designated providers shall provide a choice screen for browsers.

- When a designated business operator sets or changes the specifications, sets or changes the conditions for use, it must take necessary measures, such as securing a period for the business operator specified in each item to smoothly respond to the measure, disclosing information, and establishing a necessary system, as specified by the Fair Trade Commission rules.

This law should be in force by the end of 2025.

Australia

In 2024, the Australian government agreed to new competition laws for digital platforms.

The new laws will be based on the ACCC's recommendations in their Digital platform Services Inquiry - Interim Report No. 5 which includes:

The code of conduct for mobile OS services could require Designated Digital Platforms to allow third-party browser engines to be used on their mobile OS. This could allow third-party providers of browsers and web apps to compete on their merits.

We also consider that the additional competition measures should include the ability to provide third-party providers of apps and services with reasonable and equivalent access to hardware, software and functionality through their mobile OS.

The Australian Treasury department is conducting consultation on the proposal paper and submissions can be made until 14 February 2025.

Advocating for a Fairer and More Competitive Web in 2025

2025 promises to be a pivotal year, making it more important than ever for both developers and consumers to have strong advocacy for browser and Web App competition. We sincerely thank everyone who generously contributed their time and expertise, whether through drafting or reviewing regulatory submissions, enhancing and building our website, engaging in detailed discussions, providing invaluable feedback, or participating in conferences and meetings; and especially those who helped provide financial support in 2024. You made the web a fairer, more competitive and more exciting platform.

A special thank you goes to startsmall for their exceptionally generous donation in 2023, which continues to fund a significant portion of our work today.

If you have the opportunity, please join us in 2025!