Regulators around the world are working to address competition issues in digital markets, particularly on mobile devices. Several new laws have already been passed, including the UK’s Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act (DMCC), Japan’s Smartphone Act, and the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA). Australia and the United States are also considering similar legislation with the U.S. Department of Justice pursuing an antitrust case against Apple. Across all of these efforts, common questions arise: How should competition, user choice, and utility be balanced against security concerns? What is proportionate and necessary in relation to security? And how effective is app store review in practice?

The DMA is a helpful act to look at as it has been in force the longest and many of these other acts are loosely based on it. The DMA aims to restore contestability, interoperability, choice and fairness back to digital markets in the EU. These fundamental properties of an effectively functioning digital market have been eroded by the extreme power gatekeepers wield via their control of “core platform services”.

Under the DMA gatekeepers are only allowed to have strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures to protect the integrity of the operating system.

In order to ensure that third-party software applications or software application stores do not endanger the integrity of the hardware or operating system provided by the gatekeeper, it should be possible for the gatekeeper concerned to implement proportionate technical or contractual measures to achieve that goal if the gatekeeper demonstrates that such measures are necessary and justified and that there are no less-restrictive means to safeguard the integrity of the hardware or operating system. DMA - Recital 50

(emphasis added)

The gatekeeper shall not be prevented from taking, to the extent that they are strictly necessary and proportionate, measures to ensure that third-party software applications or software application stores do not endanger the integrity of the hardware or operating system provided by the gatekeeper, provided that such measures are duly justified by the gatekeeper.

DMA - Article 6(4)

(emphasis added)

The gatekeeper shall not be prevented from taking strictly necessary and proportionate measures to ensure that interoperability does not compromise the integrity of the operating system, virtual assistant, hardware or software features provided by the gatekeeper, provided that such measures are duly justified by the gatekeeper.

DMA - Article 6(7)

(emphasis added)

Where possible, less-restrictive security measures should be used. There is an understanding by the DMA that some security measures will restrict the ability of third parties to contest gatekeepers but that where possible that restriction should be kept to the minimum "strictly necessary" and only be allowed where it is "proportionate".

Importantly the "duly justified" means that the burden of proof is on the gatekeeper to show that their security measures are "strictly necessary" and "proportionate".

While Apple currently makes an estimated $64 billion a year from its App Store and tells The Verge it has computer automation, proprietary review tools, huge volumes of internal data, and a dedicated “Discovery Fraud team” of humans at its disposal, a single person on a laptop in his living room is finding egregious scams that Apple continues to host, and I was able to use his basic technique to do the same thing. As Apple faces down hearings in Congress and lawsuits in court, its argument that it needs to maintain total control over the iPhone app ecosystem to keep users safe doesn’t mesh with the obvious examples of grift that anyone can easily find. Sean Hollister - The Verge (April 2021)

(emphasis added)

We are concerned that in many cases Apple is stretching its rules, many of which lack any legitimate security basis, far beyond the "strictly necessary" and "proportionate" scope allowed by the DMA. Further, Apple has provided no security justification for any of its new rules.

No reasonable party objects to security measures that improve security without giving anti-competitive power to gatekeepers to block third parties from contesting their services via their platform.

In certain cases, in particular browsers, gatekeepers will need to delegate the task of protecting the user and the OS to competent third-party browser vendors. Thus, the primary security measure for browsers is vetting which browser vendors get the relevant access and revoking it if the browser vendor is significantly incompetent or malicious.

In the end, Apple deploys privacy and security justifications as an elastic shield that can stretch or contract to serve Apple’s financial and business interests.

DOJ Complaint against Apple

Ultimately, the goal is to strike a balance between genuine security protections and allowing effective competition. The right policy will allow clear rules and security measures that improve security while not allowing these measures to be used as a weapon by the gatekeeper to block competitors.

You can also download the PDF version [2.6 MB]

2. Table of Contents

Table of Contents

3. Gatekeepers should not have a Presumption of Better Security

3.1. Meta: Plain Text Passwords

3.3. Apple: XcodeGhost Malware Scandal

4. Can Gatekeepers Be Trusted to Design and Evaluate Their Own Security Measures?

4.1. Gatekeepers Cannot Be Trusted to Set the Terms of Security

5. Effective Security and Browsers

6.1. XcodeGhost Malware Scandal

6.3. Apple's Decade-Long App Review Woes

7. App Distribution Source Switching

8. Direct Download and Third-Party App Stores

9.1. Update Delays and Patch Gap

10. Safari and Chrome should be uninstallable

13. Just-in-Time (JIT) Compilation

14. Installation and Management of Web Apps

15.1. What are Phishing and Fleeceware Apps?

15.4. The Web and Web Apps are more secure

15.4.1. Tighter Permissions on APIs

15.4.4. No Expectation of Review

15.4.5. URL Verification and Phishing Detection

3. Gatekeepers should not have a Presumption of Better Security

Under the Digital Markets Act (DMA), it is both inaccurate and counterproductive to presume that gatekeepers inherently provide superior security compared to third-party providers, despite ample evidence demonstrating otherwise.

Competition drives innovation, including in security. Independent companies continuously improve their security offerings to remain competitive, and many possess expertise and resources that match or exceed those of gatekeepers. For example, Mozilla, Cloudflare, Signal, Let’s Encrypt, and 1Password have all demonstrated world-class security practices.

Gatekeepers are not immune from having security breaches and there are many high-profile examples of gatekeepers having insufficient security or security breaches including:

3.1. Meta: Plain Text Passwords

Between 2012 and 2019 Meta stored passwords for hundreds of millions of users in plain text, exposing them for years to anyone who had internal access to the files. User passwords are typically protected through hashing, a one-way cryptographic process often combined with salting, to prevent them from being recovered or reversed. However, a string of errors led certain Facebook-branded apps to leave passwords accessible to as many as 20,000 company employees. Between 200 million and 600 million Facebook users are believed to have been affected.

Hashing users’ passwords is a well known and straightforward practice with no significant downsides. This should have been a trivial security measure for Meta to have implemented across all of its software products.

The Facebook source said the investigation so far indicates between 200 million and 600 million Facebook users may have had their account passwords stored in plain text and searchable by more than 20,000 Facebook employees. The source said Facebook is still trying to determine how many passwords were exposed and for how long, but so far the inquiry has uncovered archives with plain text user passwords dating back to 2012.

My Facebook insider said access logs showed some 2,000 engineers or developers made approximately nine million internal queries for data elements that contained plain text user passwords.

Brian Krebs - Krebs On Security

Storing a password in plaintext may result in a system compromise

Open Web Application Security Project

The cost of implementing proper encryption and security measures is a fraction of what it costs to deal with a data breach involving plaintext passwords. The financial and legal ramifications are severe and long-lasting. Wendy Nather - Head of Advisory CISOs at Duo Security

Storing passwords in plaintext is like writing your bank PIN on your ATM card; it's asking for trouble. Troy Hunt - Cybersecurity expert and Founder of Have I Been Pwned

In September 2024, Meta was fined 91 million euros ($102 million) for breaking Europe's strict privacy rules. The company hadn't put enough protections in place to secure people's social media passwords.

It is widely accepted that user passwords should not be stored in plaintext, considering the risks of abuse that arise from persons accessing such data. It must be borne in mind, that the passwords the subject of consideration in this case, are particularly sensitive, as they would enable access to users' social media accounts. Deputy Commissioner Graham Doyle

(emphasis added)

3.2. Microsoft: Cloud Breach

A federal Cyber Safety Review Board wrote a scathing report on Microsoft's role in the massive data breach in July 2023.

The report found that a series of security failures at Microsoft allowed nation-state actors assessed to be affiliated with China to steal hundreds of thousands of emails from cloud customers, including federal agencies. The board concluded that Microsoft's security culture was inadequate and ill-prepared for the increasing sophistication of cyber threats.

The report details Microsoft's missteps before, during, and after the breach, labeling it a "preventable" incident.

The CSRB's conclusion is that Microsoft's security culture is ‘inadequate’ and that a ‘cascade of Microsoft's avoidable errors allowed this intrusion to succeed.’ It cites in particular:

• Lacking security practices of other cloud providers

• Failure to detect a compromise on a laptop from an employee at an acquired company before connecting it to its network

• Letting inaccurate public statements stand for months

• A ‘separate incident’ from January 2024 that, while not in the CSRB's purview, allowed another nation-state actor access to emails, code, and internal systems

• A need to ‘demonstrate the highest standards of security, accountability, and transparency.’ Kevin Purdy - ArsTechnica

Unfortunately, throughout this review, the Board identified a series of operational and strategic decisions that collectively point to a corporate culture in Microsoft that deprioritized both enterprise security investments and rigorous risk management, Cyber Safety Review Board - Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

3.3. Apple: XcodeGhost Malware Scandal

XcodeGhost iOS malware, discovered in September 2015, spread through altered copies of Apple’s Xcode development environment, and, when iOS apps were compiled, third-party code was injected into those apps. Users downloaded infected apps from the iOS App Store.

Documents revealed during the 2021 Epic Games v. Apple trial (still ongoing) show that 128 million users downloaded the more than 2,500 infected apps, about two thirds of these in China. Popular apps such as WeChat, Didi Chuxing, and Angry Birds 2, among others, were infected by XcodeGhost. These are some of the largest native apps in the world, being the equivalents of Facebook and Uber in China. WeChat, for example, has 1.36 billion users.

Apple's app review process failed spectacularly in the case of the XcodeGhost malware. This highlights the inherent limitations of app review as it's impractical for human reviewers (reportedly only 500 reviewers to review 130,000 apps per week, with only a few minutes spent per app ) to scrutinize the vast amounts of code submitted for each app and these reviewers likely did not even attempt to do so.

Even with the assistance of automated code scanning tools, which can be circumvented by various obfuscation techniques, complex malware like XcodeGhost, injected during the compilation process, can easily slip through.

There are long-standing and unresolved issues with malware, phishing apps, and fleeceware across both Apple and Google’s app stores over the past 16 years.

Apple discussed contacting users and briefly made an announcement on their China website. Shortly after, it was removed. To our knowledge, Apple never contacted users to inform them of the breach.

this decision to not notify more than 100 million users about potential security issues seems to have more to do with protecting the platform’s reputation than helping users stay safe Kirk McElhearn - Intego

(emphasis added)

What makes this example particularly egregious is the failure to notify users. Every company will have a security breach at some point in its history, but how those breaches are handled and whether the company considers customer safety or company reputation to be more important is an interesting peek into that company's psychology when it comes to security.

3.4. Google: Google+ API Bug

In 2018, Google staff discovered a bug in the Google+ API that could have been abused to steal the private data of nearly 52.5 million users.

Google said the bug allowed apps, which were granted permission to view Google+ profile data, to incorrectly receive permission to view profile information that the user had set to "not-public".

Google+ faced its second big breach of 2018 when a November update created an API bug that exposed data from 52.5 million Google+ accounts. Google fixed the bug within six days, and moved up Google+’s burial date from August to April 2019. Michael X. Heiligenstein - Firewall Times

According to Google, the bug was introduced in November 2018 during a previous platform update and was live for only six days before its engineers discovered the issue. Once fixed, Google notified end users who had been impacted and publicly disclosed the existence of the bug.

Although Google handled this vulnerability well, it illustrates that even well-resourced gatekeepers will have vulnerabilities (and even breaches) from time to time, and the important element to focus on is how they handle them and could they reasonably have prevented them.

In particular:

Did they sufficiently follow good security practices?

Did they promptly fix the vulnerability?

Did they offer a public bug bounty program?

Did they have a healthy non-adversarial relationship with security researchers?

Did they notify end users?

Did they publicly disclose the bug once fixed?

Third-party vendors should not be blocked from competing if they are doing a proportionate and effective job at security, especially if they are doing a better job than the gatekeepers, even if they have the occasional vulnerability or breach. Proportionate security is the aim, not some abstract perfect security that even well-resourced gatekeepers can not obtain.

To be clear, we are not accusing any of these gatekeepers of having poor security relative to the industry. Rather, many gatekeepers, and in particular Apple, project an image of themselves as impenetrable fortresses which is misleading and hinders constructive security discussions.

Requiring gatekeepers to justify their security claims promotes transparency and accountability, ensuring they demonstrate the effectiveness of their measures and exposing any shortcomings. Even better, third-party auditors should be able to verify security claims against cross-industry standards, such as GSMA’s (see Ian Brown’s study commissioned by Meta). By not presuming gatekeeper superiority, the DMA and other regulators can allow contestability, improve interoperability, and ensure a more secure digital marketplace for consumers.

4. Can Gatekeepers Be Trusted to Design and Evaluate Their Own Security Measures?

Gatekeepers often invoke security to justify maintaining control over their ecosystems, particularly when faced with regulatory demands to increase interoperability or promote competition.

A notable example is Apple’s response to regulatory pressure to allow competing browser engines on iOS. In submissions to the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), Apple argued that its own engine, WebKit, is inherently more secure than Blink or Gecko:

... in Apple's opinion, WebKit offers a better level of security protection than Blink and Gecko.

Apple raised a number of concerns that introducing third-party browser engines, or increasing the interoperability of WebKit, could introduce privacy and security risks. Apple submitted that Webkit offers the best level of security, and has cautioned that ‘mandating use of third-party rendering engines on iOS would break the integrated privacy, security, and performance model of iOS devices’.

UK CMA - Interim Report into Mobile Ecosystems

But the CMA found Apple’s claims unconvincing and firmly rejected them:

... the evidence that we have seen to date does not suggest that there are material differences in the security performance of WebKit and alternative browser engines.

Overall, the evidence we have received to date does not suggest that Apple's WebKit restriction allows for quicker and more effective response to security threats for dedicated browser apps on iOS.

UK CMA - Interim Report into Mobile Ecosystems

The pattern is consistent elsewhere. Both Apple and Google have blocked third-party payment systems under the pretext of security. Yet neither has proposed proportionate alternatives, such as mandating PCI-DSS compliance, using known secure providers (such as Stripe or Adyen) or establishing clear technical standards. Instead, they’ve insisted that only their proprietary systems, through which they extract up to 30% in fees, are secure.

Even longtime Apple defender John Gruber called this rationale outdated:

‘This app does not support the App Store’s private and secure payment system. It uses external purchases.’

[...]

The uncompetitive nature of the App Store — I’m using uncompetitive rather than anticompetitive just to give Apple the benefit of the doubt here — has left at least some top Apple executives hopelessly naive about the state of online payments. It’s like when they still blather on about software being sold on discs inside boxes in physical retail stores. That was true. It was once relevant. It no longer is and hasn’t been for over a decade.

Same with payments. Online payments through, say, Stripe — which zillions of companies use — are completely private and secure today. Amazon payments are completely private and secure. John Gruber - Tech Writer

(emphasis added)

Apple's abuse of the "security" excuse became especially apparent in the aftermath of its legal battle with Epic Games. Though Apple largely prevailed, the court issued an “anti-steering injunction” requiring that apps be allowed to direct users to external payment methods. The ruling left some flexibility in implementation, but Apple chose “an anti-competitive option at every step”.

Apple introduced a 27% commission on web purchases and layered on a deliberately intimidating warning screen for users leaving the app:

Rafael Onak, a user experience writing manager at Apple, instructed an employee to add the phrase “external website” to the screen because it “sounds scary, so execs will love it.” Another employee gave a suggestion on how to make the screen “even worse” by using the developer’s name, rather than the app name. “ooh - keep going,” another Apple employee responded in Slack.

Even Cook got in on the action. When he finally saw the screen for approval, he asked that another warning be added to state that Apple’s privacy and security promises would no longer apply out on the web.

In court, Apple tried to argue that the term “scary” didn’t actually mean it wanted the screen to scare people. “Scary,” it claimed, was a “term of art” — an industry term with a specialized meaning. In fact, the company claimed, “scary” meant “raising awareness and caution.” The court did not buy it, saying the argument strained “common sense.”

Jacob Kastrenakes - The Verge

Given the context above, one can conduct a thought experiment: Which of the following was Apple’s primary motivation?

Option 1: Apple was genuinely concerned that the court orders would compromise user security, which could damage its reputation. Accordingly, Apple sought to implement security measures aimed at mitigating those risks in a proportionate manner while still fully complying with the court order.

Option 2: Apple was primarily concerned that the court orders would undermine its control over App Store revenue, particularly its 30% commission, on transactions within an ecosystem worth $406 billion in 2024, and acted to discourage developers from adopting alternative payment methods and to ensure no business would be able to benefit from or attempt to exercise the rights granted under the court’s order.

Unfortunately for Apple, the answer appears painfully obvious, even to a public that is generally sympathetic to the company. Rather than engaging in serious, detailed security reviews and proposing proportionate safeguards, Apple’s internal discussions have included non-security personnel, including current Apple CEO Tim Cook, exploring how to make the alternative user experience deliberately “even worse”.

Apple also attempted to engineer the directive to allow external links in apps by creating new barriers and requirements that would similarly defang those orders. It created full-page “scare screens” (I referred to them as “This App May Kill You” screens), demanded that all links be to static URLs (neutering their utility), and kept editing the warning labels to dissuade users as much as possible from ever agreeing to follow the link. (Cook is specifically credited with amping up the language in the warning screens.)

The company’s internal struggle is fascinating to read about. While Apple Fellow and longtime App Store overseer Phil Schiller doesn’t come across entirely smelling like a rose, he does end up looking far better than literally any other Apple employee in the ruling. Schiller “advocated that Apple comply with the Injunction”—imagine that!—while Tim Cook, CFO Luca Maestri, and the company’s finance team instead decided to concoct a strategy of malicious compliance that led to the poison pill of the 27% commission. Jason Snell - Six Colors

This approach backfired on Apple when the judge found:

Apple willfully chose not to comply with this Court’s Injunction, It did so with the express intent to create new anticompetitive barriers which would, by design and in effect, maintain a valued revenue stream; a revenue stream previously found to be anticompetitive. That it thought this Court would tolerate such insubordination was a gross miscalculation. As always, the cover-up made it worse. For this Court, there is no second bite at the apple. Justice Gonzalez Rogers

The court went further, holding Apple in civil contempt for misleading the court and abusing attorney-client privilege to delay proceedings. It ordered Apple to pay Epic’s legal costs and referred the matter to federal prosecutors for potential criminal sanctions against Apple and one of its senior executives.

4.1. Gatekeepers Cannot Be Trusted to Set the Terms of Security

Gatekeepers, and Apple in particular, have consistently used “security” as a smokescreen to protect profits and block competition. Their assessments of what is “secure” or “proportionate” cannot be trusted, especially when interoperability threatens their control or revenue.

What Should Regulators Do Instead?

There are several straightforward steps that can be taken by regulators to combat this:

Allow browser vendors to use independent third-party security audits to meet gatekeeper security requirements, rather than requiring audits to be conducted or approved solely by the gatekeeper.

Dismiss unsubstantiated security claims unless backed by credible, technical evidence.

Security claims should be assessed with the assumption that reasonable security measures will be implemented.

Rely on industry bodies and external experts when gatekeepers have shown bad faith or poor judgment.

Rely on industry security standards and certifications.

5. Effective Security and Browsers

Browsers are a unique category of app, powering an entire interoperable and open ecosystem that competes with gatekeeper app stores.

Major browser vendors have dedicated security teams and, especially those involved in heavy engine development, need the ability to build their own sandboxes. Apple should allow browser vendors to port their existing sandboxes to iOS.

This is important as it changes the frame of referencing in relation to security. The question becomes not how the OS gatekeeper can protect users from the app but how can the OS gatekeeper restrict delegating this elevated responsibility of protecting the user to only those browser vendors that have the competence and reputation to be able to do it. The process becomes less about sandboxing and more about vetting who gets the browser engine entitlement or equivalents.

For example, in many cases it makes little sense for Apple to sandbox the third-party browser vendor’s (arguably superior) sandbox. Based on Apple's own analysis, this solution is obviously not viable or proportionate as it would require browser vendors to substantially redesign their own engine. Apple has a vast array of less restrictive methods, including contractual, to ensure user security.

...architecting a novel sandbox for third-party browser engines would require ground-up analyses of third-party engines with which Apple is not familiar. Third-party vendors would very likely need to substantially re-design their engines to meet iOS security and privacy requirements. Apple - Browser Vendors will need to substantially re-design their engines

(emphasis added)

That said, where OS gatekeepers can make the system significantly more secure in ways that do not impede competition, they should have no issue in proving such changes are proportionate and necessary. No reasonable browser vendor would object to such security measures and such measures meeting those conditions are allowed by the DMA. Where a security measure will impede competition, the gatekeeper should have to show extensive evidence as to why it is “strictly necessary” and “proportionate”.

Importantly, gatekeepers should not be able to reserve special setups for their own browser. Safari should be required to use BrowserEngineKit if it is imposed on other browsers. This ensures a level playing field, ensures that BrowserEngineKit is of sufficient quality to support their own browser and prevents Apple from gaining an unfair advantage.

Safari and Chrome on iOS and Android respectively should receive no additional special treatment from the OS. Note, the DMA explicitly allows them to be pre-installed so that form of privilege is allowed.

6. Is App Review Effective?

The app review process has grown in importance as Apple increasingly emphasizes its App Store services as a source of revenue and iPhone security as a key selling point.

In addition, Apple’s platform is drawing new scrutiny as politicians and regulators take a more skeptical look at the power of big tech companies.

[...]

App Review is organized under the marketing umbrella at Apple and always has been, even before Schiller took over the greater App Store marketing and product departments in late 2015.

Kif Leswing - CNBC

(emphasis added)

In recent years, Apple has more strongly stressed the security of their app store. Bizarrely, according to this CNBC article, Apple's app store review team is under the department of marketing at Apple.

However, it doesn’t even appear to be effective in picking up apps that violate Apple’s payment rules (that grant it a 15-30% stake), something they are likely to want to enforce. In one particularly striking example of app review being ineffective at blocking updates that violate the current rules of the Apple’s app store, Epic managed to slip in an entire third-party payment solution into their app without it being picked up in review.

As Apple’s head of fraud Eric Friedman said regarding review processes:

please don’t ever believe that they accomplish anything that would deter a sophisticated hacker. I consider them a wetware rate limiting service and nothing more Eric Friedman - Apple’s former head of fraud on App Store Review

This suggests that, while Apple outwardly projects confidence in the value of their app store review, some informed insiders view it as worthless.

Browsers use a far more reliable form of security than brief human review upon update.

They lock down the entire environment that the third-party code, that is websites and Web Apps, run in. This environment is called a sandbox and every action a website takes is tightly controlled. Even Apple acknowledges that browser’s sandbox is massively superior to iOS’s sandbox for native apps:

WebKit’s sandbox profile on iOS is orders of magnitude more stringent than the sandbox for native iOS apps. Apple’s Response to the CMA’s Mobile Ecosystems Market Study Interim Report

It is critical that any security threat that browsers face be viewed holistically and not in isolation. That is, were the user forced to install a native app to use that same functionality, instead of using a website or Web App, then what would their relative risk be? Would it be significantly better or worse?

One interesting example of this is that various app developers have been accused by Apple of using private APIs that they do not have permission to use. The fact that this must be picked up in review or code scanning, rather than simply not being possible, suggests an architectural flaw in the operating system.

This broader pattern of risky architectural decisions is not limited to an over-reliance on app review and code scanning. As Ian Beer of Project Zero highlights in his analysis of a kernel-level parser vulnerability:

I believe it's still quite possible for a motivated attacker with just one vulnerability to build a sufficiently powerful weird machine to completely, remotely compromise top-of-the-range iPhones.

[...]

Should such a complex parser driving multiple, complex state machines really be running in kernel context against untrusted, remote input? Ideally, no, and this was almost certainly flagged during a design review. But there are tight timing constraints for this particular feature which means isolating the parser is non-trivial. It's certainly possible, but that would be a major engineering challenge far beyond the scope of the feature itself. Ian Beer - Project Zero

(emphasis added)

Beer’s point reinforces the idea that Apple sometimes knowingly accepts unsafe architectures due to performance or engineering tradeoffs, even when the safer route is known.

There have also been many high profile cases of fleeceware or phishing on both the Apple’s iOS App Store and the Google Play Store.

6.1. XcodeGhost Malware Scandal

As discussed here, the XcodeGhost iOS malware was introduced through altered copies of Apple’s Xcode development environment and around 128 million users were impacted by more than 2,500 infected apps. Apple failed to publicly disclose the breach in detail and did not notify end users.

6.2. LassPass

Lasspass was a password app masquerading as Lastpass on Apple’s iOS App Store.

As LastPass is used to store very sensitive information, such as authentication secrets and credentials (username/email and password), the app was likely created to act as a phishing app and steal credentials. Bill Toulas - Bleeping Computer

Apple's App Store review team is notoriously fickle about the software it approves for sale. Some companies have found themselves needing to tweak, change, or even totally remove certain features in order for their app to make it through the process.

Yet, somehow, a fake LastPass app made it past this very review team. Even worse, the fraudulent version of LastPass was available for weeks before it was eventually taken down, and only after it was noticed by the LastPass team themselves. Matt Binder - Mashable

It is not hard to imagine why an app impersonating an extremely popular password manager is a security disaster, especially given that end users believe that these apps are carefully reviewed. With perfect ironic timing, this app was approved (and allegedly reviewed) by Apple just as it was railing against the DMA allowing competition for its iOS app store as being detrimental for user security. The core pillar of Apple’s arguments is that only they are able to effectively protect users from such apps.

The new options for processing payments and downloading apps on iOS open new avenues for malware, fraud and scams, illicit and harmful content, and other privacy and security threats, Apple - Statement on Jan 25th about the DMA

The app was only removed after its existence was reported in the news. Apple has offered no explanation on how they allowed this app to be approved.

6.3. Apple's Decade-Long App Review Woes

Lasspass and malware like it on Apple’s app store are not a recent problem. Problems with the human element of app store review have plagued Apple for over a decade.

What the hell is this??????

[...]

How does an obvious rip off of the super popular Temple Run, with no screen shots, garbage marketing text, and almost all 1-star ratings become the #1 free app on the store?

Can anyone see a rip off of a top selling game? Any anyone see an app that is cheating the system?

Is no one reviewing these apps? Is no one minding the store?

This is insane!!!!!!!!! Phil Schiller - Apple Senior Vice President Worldwide Marketing (Feb 2012)

Eric Friedman, who later became Apple’s head of fraud, issued a dim assessment of the quality of Apple’s app store review in 2013:

App Review is bringing a plastic butter knife to a gun fight. Investment will have to be made in making that process more robust or they will keep getting rolled. Eric Friedman - Apple Head of Fraud - On App Store Review (Oct 2013)

As late as 2015, getting in contact with Tim Cook was a viable method of getting scams removed from Apple’s app store.

Tim received a complaint about this app being a scam (doesn't do what it says, promises bonus features for 5 star reviews, creates fake marketing videos, etc). It is a great example of the stuff we should have automatic tools to find and kick out of the store. I can't believe we still don't. Many 1 star reviews, many mention 'scam' and 'fake'. Then I look at the developers other apps and see the same issue repeated.

Please look into this. I expect we need to remove the developer from our program. (and PLEASE develop a system to automatically find low rated apps and purge them!!) Phil Schiller - Apple Senior Vice President Worldwide Marketing (Mar 2015)

Eric Freidman appeared to still have a dim view in 2018 as to the quality and effectiveness of iOS app review:

As much as those guys want to help, their paycheck depends on getting apps in the door and keeping developers happy. They are more like the pretty lady who greets you with a lei at the Hawaiian airport than the drug sniffing dog who, well, never mind. ;) Eric Friedman - Apple Head of Fraud (Feb 2018)

In 2018, Herve Sibert expressed doubt that app review had improved significantly.

Allow me to express doubts about this 'lot of work'... It's almost one year since we uncovered the I4 app hidden behind a calculator with loads of downloads, and if they've made any progress then it's just not visible.

Just like in October, AppReview fails to review properly, and we just tamper with search results (which could be dangerous from a legal perspective) to try to correct. Herve Sibert - Security and Fraud Engineering Manager (Feb 2018)

Sometimes the human element of Apple's app store review can be done very fast. This 2018 email discusses spending a total of 32 seconds to review and approve two school shooting games two weeks after the deadliest mass shooting in US history. It took Apple seven months to realize their mistake.

The app was originally assigned to Armin by the TDP with instructions to reject any apps with egregious, malicious, misleading or objectionable content. So far all evidence points to Armin was going too fast and missed all the signals to reject these apps for 1.1, or at the least escalate. According to DJH it took a total of 32 seconds to approve both apps. In addition, the deadliest mass shooting in US history happened two weeks before these apps were approved on 10/18/17. Trystan Kosmynka - Apple App Review Chief (May 2018)

The key point here is that Apple has not provided extensive evidence showing that human app review is actually effective at improving security. A striking theme of the emails (by senior Apple employees, published due to the Epic vs Apple court case which unfortunately only go up to 2020) is a sense of despair at how ineffective and hopeless Apple’s app review is, which is a sharp contrast from Apple’s curated public projection of it as an invincible fortress carefully reviewed by a crack team of experts.

This false projection can actually harm security as it lulls users into a false sense of security. Users are likely to be far more trusting of apps if they believe that Apple is carefully reviewing them.

Apple recently released this blog post which states:

From 2020 through 2023, Apple prevented a combined total of over US$7 billion in potentially fraudulent transactions, including more than US$1.8 billion in 2023 alone. In the same period, Apple blocked over 14 million stolen credit cards and more than 3.3 million accounts from transacting again.

As published in its fourth annual fraud prevention analysis released today, Apple found that in 2023, it rejected more than 1.7 million app submissions for failing to meet the App Store’s stringent standards for privacy, security and content. In addition, Apple’s persistent efforts to stop and reduce fraud on the App Store resulted in the termination of nearly 374 million developer and customer accounts, and removal of close to 152 million ratings and reviews over fraud concerns. Apple - Blog post on App Store Review

This report reads as a press release. While sheer number of apps and comments removed should give some indication of the scale of the issue prior to these changes (i.e. for the first 15 years of the app store’s existence), Apple have not published any data that might give an indication as to what percentage of fraudulent apps they have removed and how long these apps have persisted on the app store.

As a point of comparison, on-device website block lists typically get updated every half an hour, while Google Safe Browsing now has realtime protection by default. This highlights the speed and responsiveness of web threat detection. In contrast, malicious apps on mobile app stores have been documented to remain accessible for weeks, months, or even years before review systems take action.

There is no discussion of refunding consumers that have been duped out of likely hundreds of millions of US dollars, downloading these apps believing Apple has carefully reviewed them and of which Apple has collected a 30% cut.

There is also no discussion of the notable recent failures such as “Lasspass”.

Absent more detailed reporting that included the following, it is very difficult to get a gauge of the degree of app store fraud and how successful Apple's new efforts in combating it have been:

How many malicious apps made it onto Apple’s app store?

A more detailed description of Apple’s app review process (currently Apple has provided no detailed description anywhere).

What was the amount of time each app managed to stay on the app store before it was detected (i.e 5% percentile, 10% percentile … 95% percentile averages)?

How many dollars have Apple’s consumers been duped out of via fleeceware in the year?

What amount of the figure did Apple refund?

Statistics on what mechanisms apps were picked up on. I.e. user/security researcher reporting vs app review vs automated code scanning etc.

The assumption from those considering Apple’s announcement, is that the above figures were not published because they are not favorable to the arguments that Apple is making.

There are similar complaints about the Google Play Store (including by Apple).

In Apple's review team's defense they have been given a near impossible task and Apple has assigned a surprisingly small number of reviewers to the task.

Apple’s App Review team of over 500 experts evaluates every single app submission — from developers around the world — before any app ever reaches users. On average, the team reviews approximately 132,500 apps a week, and in 2023, reviewed nearly 6.9 million app submissions while helping more than 192,000 developers publish their first app onto the App Store. Apple - Blog post on App Store Review

(emphasis added)

Despite Apple's label of "expert", Apple has submitted no evidence as to what this expertise is.

Few reviewers have technical backgrounds, the former employee says, and their decisions are often subjective and vary significantly between reviewers. Shubham Agarwal - Wired

(emphasis added)

This email reveals that app store reviewers are expected to work 10-hour days, five days a week. During peak periods, these hours can extend to 12 hours per day. Phil Schiller acknowledged concerns that such conditions might be perceived as exploitative, similar to a "sweat shop" environment.

The hours might be spun to make it sound like a sweat shop - which would be awful. Everyone at Apple has periods where we get into heavy workloads (myself included). At the same time we have had to cap overtime when the team wanted too much, they wanted the extra income. Phil Schiller - Apple Senior Vice President Worldwide Marketing (Jun 2019)

(emphasis added)

Considering the sheer volume of work, reviewing and responding to 50-100 app updates working 10 hour shifts, appears to be a demanding and potentially unsustainable workload. Given this, it is not surprising that so many blatantly malicious apps are slipping through.

The app store review process also does not have a good reputation among developers (including high profile ones that have been featured on the app store) or tech writers.

There are endless horror stories around curation of the store. Apps are rejected in arbitrary, capricious, irrational and inconsistent ways, often for breaking completely unwritten rules. Benedict Evans - Technology Writer

There's a lot of talk about the 30% tax that Apple takes from every app on the App Store. The time tax on their developers to deal with this unfriendly behemoth of a system is just as bad if not worse Samantha John - CEO Hopscotch

Under the DMA, gatekeepers are only allowed strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures. If they intend to impede competition from third-parties such as direct download, third-party app stores, third-party browsers and Web Apps via these security measures, then the burden is on them for each measure to prove that it is necessary and proportionate.

Apple has in effect been arguing that only they have the ability to protect users due to their “stringent standards” and “persistent efforts to stop and reduce fraud on the App Store”. But this argument loses all validity if this review is ineffective relative to automated means such as code signing and automated code checks. Further, Apple will need to prove that third-parties are unable to achieve the same or a higher standard of security. This is particularly relevant for Web Apps which rely on “orders of magnitude” superior sandboxing as opposed to a brief human review.

Finally, no reasonable party will object to security measures that improve security but do not place any anti-competitive power in Apple or Google’s hands.

7. App Distribution Source Switching

Apps, such as browsers, should be able to prompt users to change their update and distribution source – on a per-app basis, when wanted. Currently, even if other app stores become available, they are locked into continuing to use both Apple’s and Google’s app stores because of the high volume of already installed apps whose updates are distributed by these stores and the extremely high friction in switching the apps from one store to another.

This new distribution source could be either another app store or the developer directly.

Currently, the only way to switch distribution source on both iOS and Android is to delete and reinstall the app, a process that is time-consuming and risky due to potential data loss. This practice helps lock users into Google Play and Apple's app store. Friction can be a powerful barrier to competition. By making it difficult for users to switch, gatekeepers can maintain their dominant market position in the distribution of apps even after the DMA compels them to allow it due to the vast body of native apps that users have already installed from the gatekeeper’s app store.

An example prompt could be: “‘Firefox’ would like to switch its distribution source from ‘Apple App Store’ to ‘Mozilla Inc’. Changing this will mean all updates and app review will be performed by ‘Mozilla Inc’. Would you like to switch distribution source: YES | NO”

To prevent further reinforcing their dependence on the core platform services of gatekeepers, and in order to promote multi-homing, the business users of those gatekeepers should be free to promote and choose the distribution channel that they consider most appropriate for the purpose of interacting with any end users that those business users have already acquired through core platform services provided by the gatekeeper or through other channels. Digital Markets Act – Recital 40

(emphasis added)

This would lessen the ability of gatekeepers to lock existing users into their ecosystem using the significant friction the current design applies on switching.

This style of remedy is allowed by Recital 40 of the Digital Markets Act. This would help mitigate gatekeeper's ability to lock users into their ecosystem by reducing the friction associated with switching distribution sources.

8. Direct Download and Third-Party App Stores

Browser vendors have the right to distribute their browsers directly to consumers on iOS and Android. This is and should be subject to strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures as allowed under the DMA.

We also propose that a more accurate and neutral terminology should be used for alternative software distribution on mobile platforms to the gatekeepers’ app store. The term "sideloading" often evokes a sense of unauthorized or illicit activity. Additionally, the term itself suggests a "side" or "secondary" method of installation, further reinforcing the notion that it is not the standard or approved way to obtain software.

We believe the term “direct install” should be used to describe the process of obtaining native software directly from the developer over the internet. This is the primary method of software distribution on desktop computers.

For third-party app stores, we would recommend the phrase “allowing third-party app stores to compete fairly”.

Web Apps represent a third category of competition. These applications are secured and managed by the browsers that install them.

The Digital Markets Act recognizes the importance of diverse competition in the app market and directly supports, and mandates the allowance of, all three distribution models in the wording of the act. This was confirmed directly by DMA rapporteur Andreas Schwab MEP at an IMCO meeting on the DMA and app stores, responding to a question by panellist Ian Brown. Dr Schwab referred to advice he received directly on this from the European Commission’s lawyer-linguists, who translated the DMA into the official languages of the Member States.

9. Notarization

Apple currently notarizes (applies a digital signature to) apps distributed outside its app store, but has stated that this review is strictly limited to security. iOS and iPadOS will not run apps without this digital signature.

Notarization for iOS apps is a baseline review that applies to all apps, regardless of their distribution channel, focused on platform policies for security and privacy and to maintain device integrity. Through a combination of automated checks and human review, Notarization will help ensure apps are free of known malware, viruses, or other security threats, function as promised, and don’t expose users to egregious fraud. Apple – On Notarization

(emphasis added)

It's important to note that this is significantly different from macOS notarization, which is a fast and automated process. macOS notarization verifies that the developer signed the software and that the app is free from known malicious components.

Notarize your macOS software to give users more confidence that the Developer ID-signed software you distribute has been checked by Apple for malicious components. Notarization of macOS software is not App Review. The Apple notary service is an automated system that scans your software for malicious content, checks for code-signing issues, and returns the results to you quickly. If there are no issues, the notary service generates a ticket for you to staple to your software; the notary service also publishes that ticket online where Gatekeeper can find it. Apple – on macOS Notarization

(emphasis added)

Were Apple’s proposal simply to apply automatic checks including for code signatures that verify the developer is the same developer with the browser entitlement and apply quick and automated scans for known malicious code, that would be perfectly acceptable and beneficial.

However, Apple's language suggests that it will be used as a disguised form of app store review. We are concerned that not only will this grant them power to block competition, but will in fact worsen security by slowing down browser updates and worsening security. One study already found that the potential for disguised retribution by Apple by slowing approval of new apps and app updates in its App Store led even the very largest firms (designated as DMA gatekeepers) to avoid publicly criticising the company.

It is unclear that Apple’s reviewers will have anything meaningful to add to the work of the dedicated security teams of the browser vendors.

9.1. Update Delays and Patch Gap

“Patch gap” is the amount of time between a vulnerability being discovered and it being patched on consumers devices. It is a critical aspect of security that this gap is as small as possible.

Apple's past behavior, as evidenced by the DOJ complaint, raises concerns about its potential for arbitrary and significant delays to updates.

Apple suppresses such innovation through a web of contractual restrictions that it selectively enforces through its control of app distribution and its ‘app review’ process [...] Apple often claims these rules and restrictions are necessary to protect user privacy or security, but Apple’s documents tell a different story. In reality, Apple imposes certain restrictions to benefit its bottom line by thwarting direct and disruptive competition for its iPhone platform fees and/or for the importance of the iPhone platform itself. DOJ Complaint against Apple

Browser vendors have their own dedicated security teams which have worked for decades to secure their own browsers. Additionally, Apple has a worse track record than Firefox and Chrome when it comes to the patch gap, as can be shown by evidence from Google Project Zero.

We disagree with the claim that allowing third-party browsers will increase the patch gap for iOS users. Publicly available evidence suggests in fact the opposite is true and will significantly reduce the time it takes for patches to reach users.

Safari updates are tied to the operating system, an antiquated practice. This means to update the browser, users have to update the entire operating system, which further delays patches reaching users. The important metric is the time from when a vulnerability is privately reported – or discovered in the wild – to the date users are protected against a vulnerability. This is known as a “window of vulnerability”.

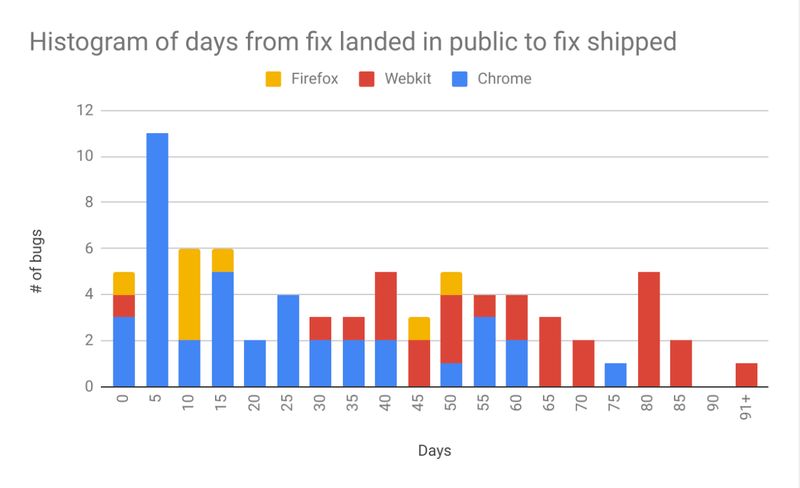

The above graph shows the number of days from a vulnerability being patched till that patch is actually shipped to consumers for Gecko, WebKit and Blink. WebKit has performed worse than its peers in this important metric.

And that gets us back to the main problem with Apple's security update policy—a lack of transparency, predictability, and communication. Andrew Cunningham - Ars Technica

For example, Apple took 59 days to land a fix regarding a serious privacy flaw in WebKit’s IndexedDB implementation. Poor communication from Apple caused the FingerprintJS team to disclose the bug before a fix had reached users. Spurred by the public disclosure, Apple quickly developed patches to address the issue, but it took an additional 10 days to package the OS update and ship it.

Leaving the window of vulnerability open this far in the face of publicly disclosed issues does much to draw into question Apple’s claims of protection. If users had credible alternative browsers available to them, they might have been able to better protect their privacy for the week and a half it took Apple to finally fix a long-disclosed issue.

The article titled "Apple’s Poor Patching Policies Potentially Make Users’ Security and Privacy Precarious” goes into more detail.

10. Safari and Chrome should be uninstallable

Under the Digital Markets Act, Apple and Google are required to allow users to uninstall Safari and Chrome on iOS and Android, respectively.

This is important to prevent gatekeepers from positioning their browser to users as “special” and the one that should be used with the operating system. This undermines users' ability to make an unbiased choice. Conversely being able to uninstall the browser however makes it clear that it is simply an app that can be replaced.

Such behaviour includes the design used by the gatekeeper, the presentation of end-user choices in a non-neutral manner, or using the structure, function or manner of operation of a user interface or a part thereof to subvert or impair user autonomy, decision-making, or choice. Digital Markets Act - Recital 70

(emphasis added)

The AndroidWebView, Android Custom Tabs, WKWebView and SFSafariViewController should be treated as system components, and it should not be possible to uninstall them.

One important condition on that is that both Android Custom Tabs and SFSafariViewController must respect the users choice of default browser and invoke the default browser with handle links clicked in non-browsers. Currently Android Custom Tabs does this in most circumstances but SFSafariViewController is locked to Safari.

We would also support it not being possible to uninstall the default browser until a new default browser has been selected. An appropriate and neutral error message should be displayed if the user attempts to do so.

Additionally it should be possible to reinstall Safari or Chrome if it is uninstalled. This reversibility is important to prevent users from being discouraged from uninstalling the browser.

On the 23rd of October 2024, Apple agreed to allow Safari to be uninstallable.

11. Browser Engine Kit

Apple should be prohibited from having a preferential setup for its own browser. The DMA Article 6(7) mandates that all operating system gatekeepers, including Apple, must share all APIs accessible to their own apps with third-party competitors, subject to strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures.

Apple should not be allowed to reserve APIs or API versions exclusively for its browser or engine. All APIs used by WebKit and Safari should be made available to third-party browsers. We are concerned that Browser Engine Kit might require third-party browsers to use different APIs than Safari/WebKit for equivalent features.

It is important that Apple "eats its own dog food" – a common tech industry saying meaning “use its own services every day”, rather than reserve the highest-quality tools for yourself. This will ensure that the APIs in browser engine kit are of sufficient quality and stability to support Webkit/Safari. It will also remove an incentive for Apple to deliberately under-invest in the quality of its open APIs relative to its own private ones.

In some cases third-party browsers may need access to APIs that Safari/WebKit does not use, for example, Safari/WebKit doesn't support the relevant functionality or achieves the same goal using different technical means. In these cases the browsers need to be granted sufficient access to effectively implement the relevant functionality.

The UK regulator agreed with this assessment in their recent Browsers and Cloud Gaming Market Investigation Reference where they stated that third-party browsers should be given equivalent access and clarified this as meaning:

(a) enabling access in a way which respects the technical architecture of alternative browser engines;

(b) enabling access to all of the current operating system-level features and functionalities that WebKit and Safari currently use;

(c) enabling access to all other current operating system-level features and functionalities that exist on iOS and are available for use by third-party applications, but which WebKit and Safari currently do not use;

(d) enabling access to future operating system-level features and functionalities available to WebKit, Safari, or third-party applications, whether or not WebKit and Safari choose to use them;

(e) enabling access to the required iOS functionality to allow browser vendors using alternative browser engines to install and manage progressive web apps (PWAs) using alternative browser engines; and

(f) enabling access to the required functionality to allow browser vendors using alternative browser engines to check whether their mobile browser has been set as default

The general concept of a collection of APIs that the browser engine entitlement grants access to in return for agreeing to a set of strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures is acceptable and reasonable. However, it is important to note that Apple's current browser engine entitlement contract contains a great many non-security conditions that may not be allowed under the DMA.

Again, giving Apple (rather than a cross-industry body) the power to decide these criteria and to judge competitors’ browser engines against them (rather than an independent auditor working to cross-industry standards, such as GSMA’s plans for mobile phone security) would give the gatekeeper a strong and perverse incentive for under-investment. In addition, any security requirements set out by Apple should also be applied to Safari. If Safari does not meet the same minimum requirements, it would be unreasonable to enforce them on other browsers. Equal enforcement is essential to ensure a level playing field.

12. Browser API Access

Browsers are special as they play a unique role in enabling more easily-developed web apps to compete with the entire native app ecosystem. They are a substitute to the gatekeeper’s app stores and offer a direct consumer-to-business relationship without excessive fees.

From a technical perspective, browsers need privileged operating system access as they power web apps, which are a substitute and competitor to the gatekeeper’s app stores' apps.

In order to allow web apps to effectively contest their native app counterparts, browsers need to provide a wide variety of functionality typically required by native apps, which is interoperable across devices. This requires access to significantly more software and hardware APIs than other applications, including features that may not be exposed by the gatekeeper within an individual ecosystem.

This access is justified by browsers' special role as the world's only truly open and interoperable app development platform, and the high security environment that browsers provide by default. According to Apple: "WebKit's sandbox profile on iOS is orders of magnitude more stringent than the sandbox for native iOS apps".

This is important as it means that Apple does not have any significant unmitigatable security objections to such a change. Apple has also been unable to prove the security of WebKit is superior to that of Blink or Gecko, and there is some evidence to suggest it might in fact be weaker.

Apple had claimed that Safari’s engine’s security was better than that of third-party browsers. This was alluded to in the CMA’s interim report:

in Apple's opinion, WebKit offers a better level of security protection than Blink and Gecko. CMA - Quoting Apple on WebKit security

The CMA rejected this claim stating:

the evidence that we have seen to date does not suggest that there are material differences in the security performance of WebKit and alternative browser engines. [...] Overall, the evidence we have received to date does not suggest that Apple's WebKit restriction allows for quicker and more effective response to security threats for dedicated browser apps on iOS CMA - Commenting upon Apple’s Arguments

Apple has also argued that Safari's enhanced security was in part a result of its decision to withhold certain security-related APIs from its competitors. The company used this as a justification for limiting the ability of third-party browser vendors to compete on iOS with their own rendering engines. However, Apple's legal team appeared to miss the straightforward solution of sharing these APIs with other browser vendors, which would have addressed this security concern while still allowing fair competition.

WebKit leverages tight integration with iOS hardware. Apple employs a highly effective hardware security extension (APRR) to prevent attackers gaining access to the JIT. Apple also implements Pointer Authentication Codes (PAC) to prevent attackers from gaining code execution outside of the JIT. PACs provide cryptographic signatures and authentication to function pointers and return addresses to protect against the exploitation of memory corruption bugs

[...]

third-party vendors’ browser engines would lack important features and security protections that WebKit gains from its tight integration with Apple Silicon and iOS. For example, no third-party engine would offer PACs. More critically, no third-party engine would offer an equivalent to the hardened sandbox profile resulting from WebKit’s integration with iOS to protect against malicious web-based attacks. Apple’s response to the CMA’s interim report

(emphasis added)

Note this was in response to the UK regulator. Under the DMA Apple is required to share hardware and software APIs, subject to strictly necessary, proportionate and justified security measures.

Browsers have dedicated, experienced security teams and should have a presumption of access to necessary software and hardware functionality for the purposes of implementing web specifications – particularly those developed by independent standards organisations (which comply with best practice, such as the EU’s Standardisation Regulation)

Article 6(7) of the DMA obliges Apple and Google to provide access to all software and hardware APIs that are available or used by the gatekeeper’s services or hardware provided by the gatekeeper regardless of whether they are part of the operating system when providing such services:

The gatekeeper shall allow providers of services and providers of hardware, free of charge, effective interoperability with, and access for the purposes of interoperability to, the same hardware and software features accessed or controlled via the operating system or virtual assistant listed in the designation decision pursuant to Article 3(9) as are available to services or hardware provided by the gatekeeper. Furthermore, the gatekeeper shall allow business users and alternative providers of services provided together with, or in support of, core platform services, free of charge, effective interoperability with, and access for the purposes of interoperability to, the same operating system, hardware or software features, regardless of whether those features are part of the operating system, as are available to, or used by, that gatekeeper when providing such services. DMA - Article 6(7)

In this instance the primary security measure is vetting to provide the browser entitlement and revoking it when abused. The browser is a trusted party that implements its own very significant sandboxing. This access can be safely provided, and is justified by the benefits to businesses, consumers and competition in general.

Browsers need access to everything that they reasonably need to implement features, stability, performance, functionality, security and privacy. This is needed to allow fair competition.

13. Just-in-Time (JIT) Compilation

All major browsers have dedicated security teams. Apple has been unable to prove that Safari or WebKit are actually more secure than its competitors and this claim has been rejected by the UK regulator. They have also claimed that third-parties will be unable to as securely implement JIT due to Apple refusing to share particular security related APIs.

Given this Apple has no “strictly necessary, proportionate and justified” reason to block third-party browsers with the browser engine entitlement from competing in the provision of JIT and to our knowledge and to Apple’s credit, they made no attempt to do so.

Note: Windows, Linux, MacOS, ChromeOS and Android allow JIT for all browsers.

Having multiple competing browsers on iOS will improve security. If a major security issue arises in Safari, consumers could switch to a different browser while waiting for Safari to be patched, which requires a full OS update. This will directly encourage better competition among browsers to improve their security on iOS.

Requiring JIT support by dominant operating systems will make it much easier for developers to write cross-platform apps which can compete on a nearly level playing-field with native apps.

14. Installation and Management of Web Apps

“Certain services provided together with, or in support of, relevant core platform services of the gatekeeper, such as identification services, web browser engines, payment services or technical services that support the provision of payment services, such as payment systems for in-app purchases, are crucial for business users to conduct their business and allow them to optimise services. In particular, each browser is built on a web browser engine, which is responsible for key browser functionality such as speed, reliability and web compatibility. When gatekeepers operate and impose web browser engines, they are in a position to determine the functionality and standards that will apply not only to their own web browsers, but also to competing web browsers and, in turn, to web software applications. Gatekeepers should therefore not use their position to require their dependent business users to use any of the services provided together with, or in support of, core platform services by the gatekeeper itself as part of the provision of services or products by those business users.”

That is, part of the purpose of Article 5(7) in preventing gatekeepers from imposing browser engines (which only Apple currently does) is to prevent gatekeepers from determining the functionality available to all browsers on the operating system and in turn web software applications.

In order for third-party browsers on iOS to deliver better web app functionality than what Apple supplies via Safari, Apple needs to allow third-party browsers to install and manage Web Apps using their own browser engine.

Web apps are interoperable, open and have no gatekeeper fees attached to them. They fit neatly into the aims of the DMA to encourage interoperability, fairness and contestability. In order to allow businesses and consumers to enjoy the full benefits of their rights under DMA Article 5(7), the European Commission should take the steps we describe in this document, as they fully developed this requirement in relation to Article 6(7), with their first technical specification under the DMA.

The UK’s CMA has also highlighted the importance of allowing third-party browsers to install web apps with their own engine in both their Browsers and Cloud Gaming MIR and their SMS investigation into Apple and Google.

For example, ‘equivalence of access’ would need to include enabling third-party browsers using alternative browser engines to install and manage PWAs (rather than relying on WebKit to support parts of this process), including enabling mobile browsers using alternative browser engines to implement installation prompts for PWAs. MIR - Provisional Decision Report

A number of the above requirements would need to be complemented by ensuring Apple: (i) permits browser apps to use alternative browser engines; and (ii) enables browser vendors using alternative browser engines to install and manage progressive web apps SMS Investigation into Apple and Google

15. Phishing and Fleeceware

15.1. What are Phishing and Fleeceware Apps?

Fleeceware is a type of malware mobile application that comes with hidden, excessive subscription fees or services that don’t exist or are available for free, i.e. with the operating system.

Phishing apps are apps designed to trick you into providing personal information, typically by impersonating a known company or app.

Both the Google Play Store and the Apple App Store have extensive and persistent problems with both types of malicious apps. These types of apps are illegal under consumer protection laws in many jurisdictions, and are also subject to enforcement under the EU’s Digital Services Act which applies to any platform serving EU residents, regardless of where the app developer or app store is based.

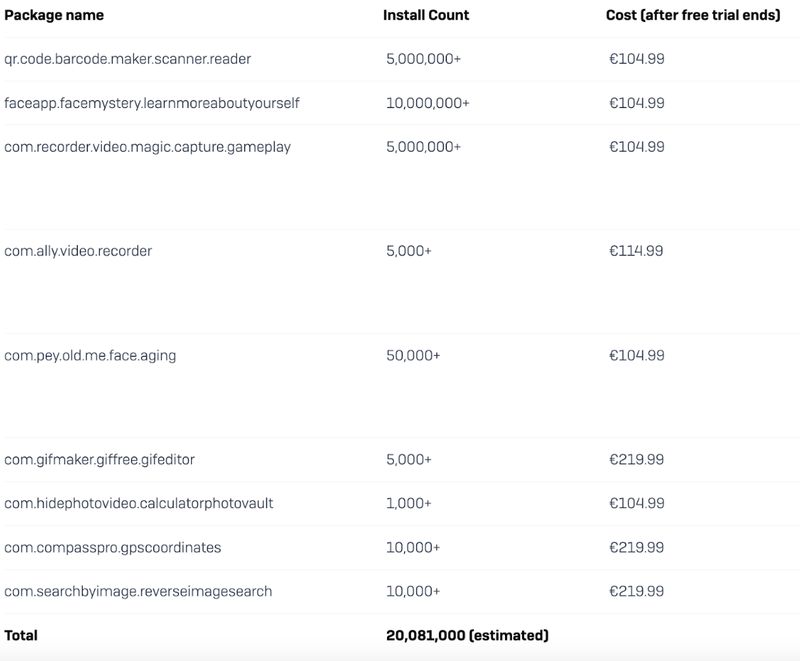

15.2. Fleeceware

Researchers at Avast have discovered a total of 204 fleeceware applications with over a billion downloads and over $400 million in revenue on the Apple App Store and Google Play Store. The purpose of these applications is to draw users into a free trial to 'test' the app, after which they overcharge them through subscriptions which sometimes run as high as $3,432 per year. These applications generally have no unique functionality and are merely conduits for fleeceware scams. Avast has reported the fleeceware applications to both Apple and Google for review.

The fleeceware applications discovered consist predominantly of musical instrument apps, palm readers, image editors, camera filters, fortune tellers, QR code and PDF readers, and ‘slime simulators’. While the applications generally fulfil their intended purpose, it is unlikely that a user would knowingly want to pay such a significant recurring fee for these applications, especially when there are cheaper or even free alternatives on the market. Jakub Vávra - Avast

The above reporting would mean that between them Apple and Google directly made $130 million on just the fleeceware apps discovered and reported by Avast. To our knowledge neither company refunds money gained from fleeceware.

This incredible email and pdf is worth a read to understand how fleeceware works on the iOS app store.

A step-by-step guide to a $500k/month scam:

Step 1. Identify things people search and get for free on the internet

Step 2. Never produce any of this content but instead get it for free on the internet

Step 3. Build a cheap, low quality app and add the free content

Step 4. Falsely advertise free stuff though Apple Search Ads

Step 5. Make thousands of users pay $100s without knowing

Step 6. Scam user ratings so you don't get caught (breaking all of Apple's guidelines) Email to Trystan Kosmynka - Apple App Review Chief

Part of the issue that allows such scams to thrive isn’t just that app review is ineffective, it's also that by design it's easy to sign up for subscriptions for a trial and awkward to unsubscribe.

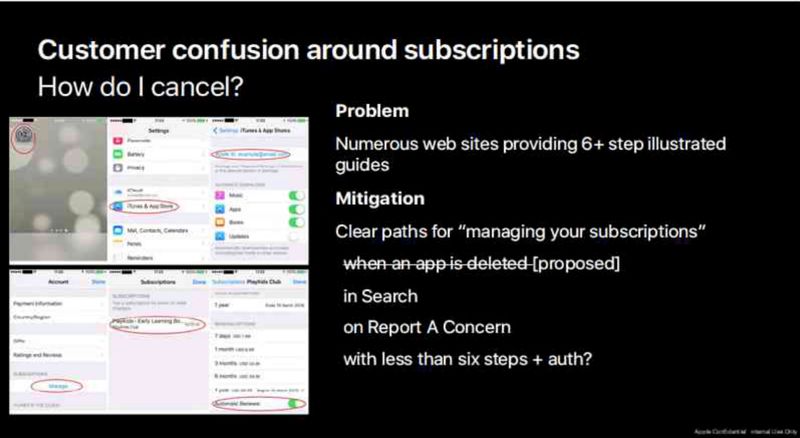

This is discussed in this email by Eric Friedman (Apple’s Head of Fraud) which mentions “clear paths for managing your subscriptions” and how the confusion interface helps such scams. In particular searching for “cancel subscription” yielded no results and deleting an app should cancel its subscription.

What is particularly striking about fleeceware apps and phishing apps, is that they are one of the few types of malware that human review might actually be potentially helpful as even a brief review (involving clicking around the interface) should reveal them to be scams – but even at this task the human review element of app store review appears to be failing.

There are some very basic steps that Apple and Google could take to help reduce the amount of malware and fraud on the Apple iOS app store and the Google Play Store:

Cancel subscriptions (or at least prompt) upon deleting an app (Apple and Google)

Ask if users would like to convert their free trial to a paying subscription at the end of the trail (Apple and Google)

Allow users to report malware in the app store (Apple)

If an app is found to be malware, investigate other apps by the same developer (Apple)

Refund money lost to obvious fleeceware scams - or at a minimum, refund the 30% cut the gatekeeper takes (Apple and Google)

15.3. Phishing

Even services such as iCloud are not immune to phishing attacks. Most infamous has been the 2014 iCloud phishing attack, when nearly 500 private pictures of various celebrities, mostly women (many containing nudity) were posted online.

Collins allegedly sent e-mails to the victims that appeared to come from Google or Apple, warning the victims that their accounts might be compromised, and asking for their login details. The victims would enter their password information. Having gained access to the e-mail address, Collins was able to download e-mails, and get further access to other files, such as iCloud accounts.

According to the prosecutors, he was able to access more than 120 different Gmail and iCloud accounts, and he is being tried for a felony violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Haje Jan Kamps - TechCrunch

To be clear, this is not to suggest any wrongdoing on Apple’s behalf, but it highlights how difficult it is to protect users from phishing attacks even in relatively secure systems. In this case the users were tricking into emailing their passwords to the attacker:

We wanted to provide an update to our investigation into the theft of photos of certain celebrities. When we learned of the theft, we were outraged and immediately mobilized Apple’s engineers to discover the source. Our customers’ privacy and security are of utmost importance to us. After more than 40 hours of investigation, we have discovered that certain celebrity accounts were compromised by a very targeted attack on user names, passwords and security questions, a practice that has become all too common on the Internet. None of the cases we have investigated has resulted from any breach in any of Apple’s systems including iCloud® or Find my iPhone. We are continuing to work with law enforcement to help identify the criminals involved. Apple’s Statement on the iCloud Phishing Attack

15.4. The Web and Web Apps are more secure

15.4.1. Tighter Permissions on APIs

The most dangerous feature that browsers have are not the device API’s; it is the ability to link to and download native apps. Niels Leenheer - HTML5test

Apple has rejected certain web standard device APIs such as Web Bluetooth, that would provide Web Apps equivalent capabilities to Native Apps:

Finally, if we find that features and web APIs increase fingerprintability and offer no safe way to protect our users, we will not implement them until we or others have found a good way to reduce that fingerprintability. Apple - Webkit Engineer

Further, via their browser engine ban, they have blocked third-party browsers from being able to safely provide the functionality.

This de-facto forces users to install an equivalent native app over a Web App if that API is a key part of the functionality offered by the app.

As a result an obvious comparison arises as to the level of security and privacy protection that goes into Web APIs vs Native APIs.

The security risks of device APIs, for both Web Apps and Native Apps, are real. Browser vendors go to extreme lengths to mitigate them. Obviously, not having these APIs is safer, in the same sense that it would be safer to entirely remove the functionality from the hardware. For example it is impossible for a phone without a camera to secretly take photos of you.

There is an inherent opposition between utility and security. What is important is to maximise utility while taking all proportionate steps to mitigate security risks.

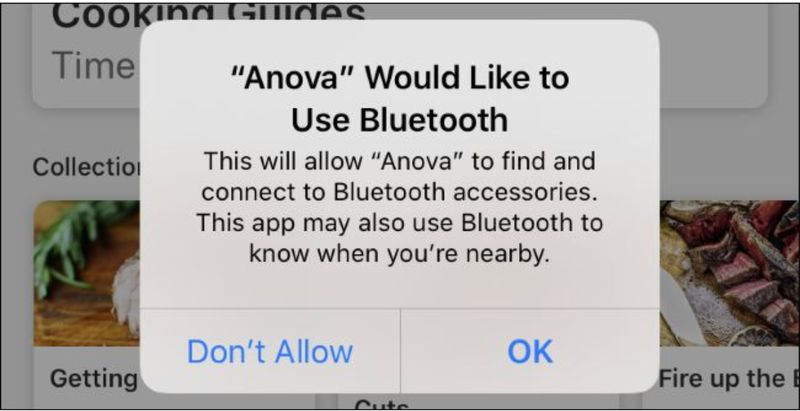

Browser vendors care deeply about these risks and discuss them, including built-in mitigations, extensively when designing APIs. For example, a number of potential security and privacy issues have been raised by participants in the Working Group developing the Web Bluetooth standard.

In order to mitigate these risks, rigorous analysis led to industry-leading constraints on the use of potentially identifiable information:

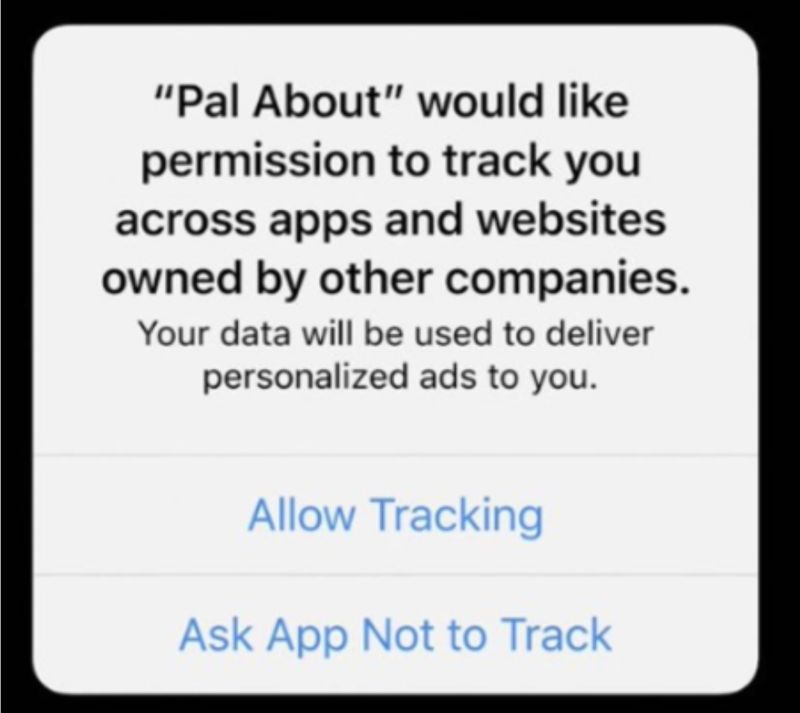

Web Apps can not get a list of bluetooth devices.