Last week, OWA was invited to attend and give a short speech on our views of Apple’s compliance with the Digital Markets Act (DMA) at a meeting with the Working Group on the Implementation of the Digital Markets Act.

The Working Group on the Implementation of the Digital Markets Act is a body within the European Parliament that monitors, scrutinises, and reports on how the DMA is being put into practice. It is currently chaired by Member of the European Parliament Andreas Schwab.

Work on the implementation of the DMA is just starting. We're here to make sure the work gets done Mr Andreas Schwab - Member of the European Parliament (September 2023)

Our Speech

The Web

Hi all, pleasure to be here, I’m Alex Moore, the Executive Director of Open Web Advocacy.

Open Web Advocacy is a global non-profit, made up of software engineers, that works to make sure the Web can compete fairly on all platforms.

The open web is essential to a free European society. It enables every EU consumer and business to connect and transact without living under the thumb of tech giants. Its strength is that it is ubiquitous, built on open standards and free from gatekeeper control. If you want to reach users on every device without gatekeepers telling you how to run your business, the web is your only choice.

Apple understands well the power of the open web, in fact, they launched the iPhone with the key promise of having a 'full browser'.

But now, on Apple’s mobile operating system, the Web is blocked from reaching its full potential. Apple prevents third-party browsers from using their own engines, underinvests in its own browser Safari, and hides the option to install web apps that compete with its own app store.

The Digital Markets Act

Luckily, the EU already has the answer: the Digital Markets Act. Article 5(7) of the Act clearly and explicitly prohibits Apple’s browser engine ban with the aim of preventing Apple from artificially limiting web software applications speed, performance and functionality.

That is, the DMA explicitly aims to allow the Web to compete fairly.

DMA enforcement is slow, deliberate and careful, but it is working and we are seeing results. The browser choice screen, for example, has helped smaller browsers grow, with Mozilla doubling daily users in France and Germany. Apple has also made it easier to change default apps worldwide in response to the DMA. In addition, the Commission has launched an interoperability process to push Apple to open up features they had previously kept to themselves.

Apple is Obstructionist

Apple, however, is taking a belligerent and obstructionist approach to the DMA. With a three trillion dollar market value and over 1 billion dollars a year in legal spending, Apple has legal power that outstrips that of small nations. It is also not afraid to step as close to the line of non-compliance as possible. As Apple’s former general counsel Bruce Sewell explained, the strategy when he was at Apple was to steer as close to the line as possible because “that’s where the competitive advantage occurs”, and even large fines are seen as acceptable costs.

Take third-party browser engines on iOS. Nineteen months after the start of DMA compliance, they are still missing. Apple requires browser makers to restart from zero users if they want to use their own engines, and at one point blocked browser vendors from even testing their own browsers outside the EU. It is still unclear whether these browsers will continue to work when EU users travel. These conditions and many others make it impossible for competitors to invest in porting their engines to iOS.

This means that EU consumers and EU businesses lose. They lose by having lower quality, less interoperable browsers with poorer support for web apps. This in turn denies a competitor to both Apple’s and Google’s app stores, which raises costs and lowers quality, and damages security and privacy across the entire mobile app ecosystem.

Innovation

Apple may claim that competition laws block innovation, but most innovation comes from small tech, not the monopolists. At one point Apple was an incredible innovator, but that time is long past. Apple hasn't had a hit new product in over a decade.

They now extract additional revenue from devices they have already sold to consumers at incredibly profitable margins, not by merit, but by the ability to block any form of installation that does not go via their app store, in some cases blocking competitors altogether.

Their fastest growing revenue source is services, that they either self-preference or simply block others from competing with.

Withholding Functionality

Apple has threatened to withhold functionality, such as Apple Intelligence or AirPods Live Translate. Regardless of what they ship, Apple must not be allowed to prevent other companies from filling the demand.

Interoperability is the key to allowing this. If Apple is unable or unwilling to ship a new feature or service in the EU, then European companies must be allowed to fill that gap.

In reality this is a bluff. Some features Apple claims to be holding back, like Apple Intelligence, have been widely criticized as not actually working. And while Apple may sometimes delay the occasional token feature in order to suggest that competition laws create problems for EU users, Apple is not going to give up its strong position to competitors, nor will it seriously risk damaging its profitable iPhone sales in the EU.

These games only work when consumers side with Apple. But judging from the online reactions to Apple’s recent call for the EU to repeal the DMA, consumers have seen through the tactic.

Security

Apple often argues that competition rules would undermine user security and privacy.

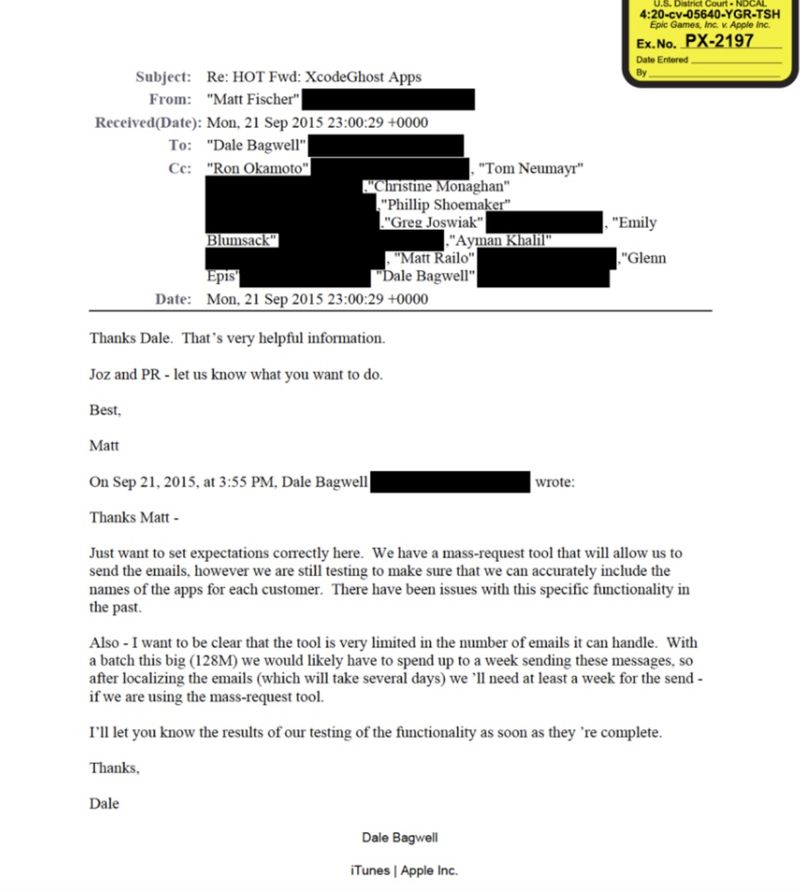

The company recently asserted that “there has never been a successful, widespread malware attack against iPhone”. That is simply a lie. In September 2015, the XcodeGhost malware infected more than 2500 apps on Apple’s app store and over 128 million iOS devices. The scale of the incident only became known years later through disclosures in the Apple-Epic court case. The issue is not Apple’s technical capacity to provide security, but its willingness to misrepresent the facts when convenient for its legal and regulatory agenda.

Apple also exempts itself from its own privacy rules by labeling its services as “first party”. But this data collection which Apple also uses for advertising is no less intrusive simply because Apple is conducting it. The US Department of Justice in their complaint against Apple stated “In the end, Apple deploys privacy and security justifications as an elastic shield that can stretch or contract to serve Apple's financial and business interests”.

Finally, Apple insists that only it can adequately safeguard users. Yet in regulatory proceedings, such as with the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority over browser security, it has repeatedly failed to demonstrate that its software is inherently more secure than alternatives.

Global and How to Fix?

At the recent DMA workshop, Apple claimed they would not "export a European law to other jurisdictions". However, Apple has, in fact, already extended several EU-driven regulatory benefits globally, including USB-C charging for iPhones, support for game emulators, NFC access for third-party payments, the new default apps page and no longer hiding the option to change default browser if Safari was already the default.

These benefits are real, they are tangible and they are spreading globally.

Outside the EU, regulators and governments in the UK, the US, Japan, Brazil, South Korea and Australia are closely watching what the EU has achieved. Many have already passed laws, are in the process of doing so, or have opened investigations against Apple on these very issues.

To ensure the Digital Markets Act delivers on its promise, the EU should:

- Keep supporting and enforcing the DMA.

- Prioritize competition and interoperability as the main drivers of growth and innovation.

- Significantly increase the DMA enforcement budget to allow more open cases.

- Investigate the deliberate slow-walking and delays in compliance and update the DMA to deter these tactics.

- And finally, don't be afraid to fine these tech giants when they blatantly circumvent EU law.

These fines must be meaningful, not just a manageable business expense for the world’s largest companies. The DMA will succeed only when it's clear to these gatekeepers that true lasting compliance is the best and only path to their achieving their goal of profit maximization.

Alongside many other civil society organisations, OWA stands firmly behind the DMA and behind the fair, open digital future it represents.

Thank you

Additional Notes

Browser Engines and the DMA

Apple’s representatives have argued that browser vendors can port their own engines to iOS in the EU and at a highly superficial and technical level this is true. However, what Apple does not acknowledge is that the conditions it imposes make doing so financially unviable in practice. Does this really count as compliance?

To answer that, we need to examine the DMA itself. The primary relevant article in the Digital Markets Act is Article 5(7):

The gatekeeper shall not require end users to use, or business users to use, to offer, or to interoperate with, an identification service, a web browser engine or a payment service, or technical services that support the provision of payment services, such as payment systems for in-app purchases, of that gatekeeper in the context of services provided by the business users using that gatekeeper’s core platform services. Article 5(7) - Digital Markets Act

(emphasis added)

At face value, Apple appears to have complied with the letter of Article 5(7). It technically allows third-party engines, but only under technical platform constraints and contractual conditions that render porting non-viable. But the DMA demands more than surface-level compliance

The gatekeeper shall ensure and demonstrate compliance with the obligations laid down in Articles 5, 6 and 7 of this Regulation. The measures implemented by the gatekeeper to ensure compliance with those Articles shall be effective in achieving the objectives of this Regulation and of the relevant obligation. Article 8(1) - Digital Markets Act

(emphasis added)

The gatekeeper shall not engage in any behaviour that undermines effective compliance with the obligations of Articles 5, 6 and 7 regardless of whether that behaviour is of a contractual, commercial or technical nature, or of any other nature, or consists in the use of behavioural techniques or interface design. Article 13(4) - Digital Markets Act

(emphasis added)

These two articles clarify that it is not enough for Apple to simply allow alternative engines in theory. The measures must be effective in achieving the article’s objectives, and Apple must not undermine those objectives by technical or contractual means.

The intent of Article 5(7) is laid out clearly in the recitals of the DMA:

In particular, each browser is built on a web browser engine, which is responsible for key browser functionality such as speed, reliability and web compatibility. When gatekeepers operate and impose web browser engines, they are in a position to determine the functionality and standards that will apply not only to their own web browsers, but also to competing web browsers and, in turn, to web software applications. Gatekeepers should therefore not use their position to require their dependent business users to use any of the services provided together with, or in support of, core platform services by the gatekeeper itself as part of the provision of services or products by those business users. Recital 43 - Digital Markets Act

(emphasis added)

In other words, Apple should not be in a position to dictate what features, performance, or standards in competing browsers and web apps they power. That is, the intent is to guarantee that browser vendors have the freedom to implement their own engines, thereby removing Apple’s ability to control the performance, features, and standards of competing browsers and the web apps built on them.

So is Apple complying in practice?

Fifteen months since the DMA came into force, no browser vendor has successfully ported a competing engine to iOS. The financial, technical, and contractual barriers Apple has put in place remain insurmountable. These restrictions are not grounded in strictly necessary or proportionate security justifications.

This is not what effective compliance looks like. Article 5(7)’s goals, enabling engine-level competition and freeing web apps from Apple’s ceiling on functionality and stability, have not been met. Under Article 8(1) and Article 13(4), that makes Apple non-compliant.

For a far more extensive analysis please read our article “Apple's Browser Engine Ban Persists, Even Under the DMA”.

Apple’s New Interop Process

The EU Commission has imposed an interoperability process on Apple due to a repeated failure by Apple to both share reserved functionality and a slow-walking of existing requests.

Apple informed the Commission that it has moved some of the aforementioned requests to 'the next phase of the interoperability process.' (11) (12) At the same time, Apple is 'still undertaking an assessment' of other interoperability requests made pursuant to Article 6(7) of Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 and has not yet moved these to the 'next phase' of Apple’s own review process. Decision to a Specification Proceeding into Apple for Connected Devices

(emphasis added)

For example, in relation to interoperability for third-party devices, Apple slow-walked their request process for over 9 months. The requests mentioned date back as far as March 2024, yet Apple neither implemented nor formally rejected them.

Under the new process, third parties have the right to file interoperability requests with Apple under Article 6(7) of the DMA. These requests can be for any software or hardware feature available on iOS and iPadOS. This includes even subsets of features, i.e. if Apple is reserving a better version for its own apps, services or devices, as well as, third-party devices interoperating with iOS or iPadOS.

Apple is only obligated to provide access to this functionality within the EU. While Apple has attempted to use this to deny companies from providing the functionality to their existing EU users, we believe that this is a circumvention of the DMA.

Interop Request Process

The request process follows 3 phases:

Phase I – Eligibility phase: Apple assesses the eligibility request to ensure that the requests fit within the scope. Must be completed within 20 days.

Phase II – Project Plan: The Project Plan should be completed by Apple within 40 working days, starting from the end of phase I. Apple should communicate the project plan to the developer who will have the opportunity to provide its feedback on it.

Phase III – Development: to establish a predictable and reliable timeline for the development phase. Apple should develop interoperability solutions that require minor, mild, and significant efforts within 6, 12, or 18 months from the submission of the interoperability request, respectively.

Under the DMA, Apple can attach security measures when it opens up access to a particular feature in order to protect the integrity of the operating system. However, these must be justified by Apple and must be objective. This document has a lot of discussion as to exactly what this means.

If you are a third-party company or developer that requires functionality that Apple currently reserves for itself in the EU to make your apps or devices better (or possible), then you can follow this process and make an interop request. All of these requests can be done at a non-legal technical level, as just polite technical requests for required functionality. Apple is not allowed to ignore these requests and must respond in writing within the above time limits.

XcodeGhost

As mentioned in the speech, Apple recently claimed that “there has never been a successful, widespread malware attack against iPhone”. We describe this statement as a lie rather than a mistake for the following reasons:

It was demonstrably malware.

With 128 million affected users and 2,500 compromised apps, it qualifies as both successful and widespread.

It is impossible to believe that the authors and reviewers of Apple’s statement were unaware of what is likely the largest and most significant malware attack in iOS history.

Even if Apple were to claim this was an honest error, which they have not, they have known about this for at least a week and have yet to correct their article.

XcodeGhost iOS malware, discovered in September 2015, spread through altered copies of Apple’s Xcode development environment, and, when iOS apps were compiled, third-party code was injected into those apps. Users downloaded infected apps from the iOS app store.

Documents revealed during the 2021 Epic Games v. Apple trial (still ongoing) show that 128 million users downloaded the more than 2,500 infected apps, about two thirds of these in China. Popular apps such as WeChat, Didi Chuxing, and Angry Birds 2, among others, were infected by XcodeGhost. These are some of the largest native apps in the world, being the equivalents of Facebook and Uber in China. WeChat, for example, has 1.36 billion users.

Apple's app review process failed spectacularly in the case of the XcodeGhost malware. This highlights the inherent limitations of app review as it's impractical for human reviewers (reportedly only 500 reviewers to review 130,000 apps per week, with only a few minutes spent per app ) to scrutinize the vast amounts of code submitted for each app and these reviewers likely did not even attempt to do so.

Even with the assistance of automated code scanning tools, which can be circumvented by various obfuscation techniques, complex malware like XcodeGhost, injected during the compilation process, can easily slip through contributing to ongoing unresolved issues with malware, phishing apps, and fleeceware in both Apple and Google’s app stores over the past 16 years.

Apple discussed contacting users and briefly made an announcement on their China website. To our knowledge, Apple never contacted users to inform them of the breach.

this decision to not notify more than 100 million users about potential security issues seems to have more to do with protecting the platform’s reputation than helping users stay safe Kirk McElhearn - Intego

(emphasis added)

Alas, all appearances are that Apple never followed through on its plans. An Apple representative could point to no evidence that such an email was ever sent. Statements the representative sent on background—meaning I’m not permitted to quote them—noted that Apple instead published only this now-deleted post. Dan Goodin - ArsTechnica

What makes this example particularly egregious is the failure to notify users. Every company will have a security breach at some point in its history, but how those breaches are handled and whether the company considers customer safety or company reputation to be more important is an interesting peek into that company's psychology when it comes to security.

Browser Security

Apple has claimed that Safari’s engine’s security is better than that of third-party browsers. This was alluded to in the CMA’s interim report:

in Apple's opinion, WebKit offers a better level of security protection than Blink and Gecko. CMA - Quoting Apple on WebKit security

The CMA rejected this claim stating:

the evidence that we have seen to date does not suggest that there are material differences in the security performance of WebKit and alternative browser engines. [...] Overall, the evidence we have received to date does not suggest that Apple's WebKit restriction allows for quicker and more effective response to security threats for dedicated browser apps on iOS CMA - Commenting upon Apple’s Arguments

This is important, as we should not give Apple a presumption of superior security. There are also arguments that Apple’s security is arguably weaker than that of other browser vendors.

Apple, First-Party and Privacy

Apple self-preferences itself by exempting itself from its own privacy rules, by arguing that its tracking for the purpose of advertising, is not tracking, as Apple is “first-party”. The UK’s competition and markets authority cover this extensively in their reports:

Apple offered the following definition of ‘tracking’ which it said was consistent with that of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C): ‘Tracking refers to the act of linking user or device data collected from your app with user or device data collected from other companies’ apps, websites, or offline properties for targeted advertising or advertising measurement purposes. Tracking also refers to sharing user or device data with data brokers.’ As detailed in Appendix J, Apple does not consider the processing activities it undertakes in terms of personalised advertising (ie use of first-party data from different Apple apps and services) as ‘tracking’, particularly as it does not link information collected by apps from different companies, and therefore its apps are not required to show the ATT prompt. This is factually correct, given that, as detailed above, Apple uses data it collects from its own services which it operates under a single corporate ownership for personalised advertising purposes.

However, as further discussed in Appendix J, based on our consideration of the ICO’s definition of online tracking, which does not distinguish between first-party and third-party data, we consider Apple’s own use of its users’ personal data no less consistent with this description of ‘tracking’ than that of third-party developers. CMA - Mobile ecosystems - Market Study Final Report

Apple does, however, use its first-party data from across multiple Apple apps for advertising purposes. For instance, Apple processes a user’s App Store purchase history, together with other demographics, to personalise App Store Search Ads and advertising displayed in the News and Stocks apps. CMA - Appendix I: considering the design and impacts on competition of Apple’s ATT changes

With regards to targeting, Apple’s advertising services are advantaged by the distinction made between first-party and third-party data sharing in the ATT framework which gives Apple licence to use a wide range of data that it treats as ‘first-party’, potentially coming from a range of Apple’s different apps and services as well as from user activity within third-party apps. Moreover, the differences between the ATT prompt and the Personalised Ads prompt discussed above make it in principle easier for Apple to be able to access user data to target its ads, relative to third parties.

CMA - Mobile ecosystems - Market Study Final Report

Apple pulls in an astonishing amount from advertising. From non-Google ad revenue alone, Apple is estimated to have earned $10.34 billion in 2024.

While the iPhone maker does not disclose its advertising revenue separately, analytics firm eMarketer estimates Apple's ad revenues could total $10.34 billion in 2024. Arsheeya Bajwa, Harshita Mary Varghese - Reuters

Combined with the estimated $20 billion per year that Apple collects from its Google Search deal, that places Apple’s annual advertising revenue at approximately $30 billion per year. This would place Apple as roughly the 5th largest firm by advertising revenue in the world after Google, Meta, Amazon, ByteDance.

In 2022 the French France’s data protection watchdog, the CNIL, concluded an investigation into Apple on App Tracking Transparency (ATT) and fined them €8,000,000 for infringing Article 82 of the French Data Protection Act due to not asking consent from users for its own applications. Later, France’s competition regulator, Autorité de la concurrence, would then go on to fine them an additional €150 million for abusive and self-preferencing ATT implementation in 2023.

Lastly, the Autorité found an asymmetry in how Apple treated itself and how publishers were treated. While publishers were required to obtain double consent from users for tracking on third-party sites and applications, Apple did not ask for consent from users of its own applications (until the implementation of iOS 15). Due to this asymmetry, the CNIL fined Apple for infringing Article 82 of the French Data Protection Act, which transposes the ePrivacy Directive.

[...]

In view of the seriousness of the facts, the duration of the infringement (between 26 April 2021 and 25 July 2023) and Apple’s economic power, the Autorité has decided to impose a fine of €150,000,000 on Apple Distribution International Limited (ADI) and Apple Inc., as perpetrators, and Apple Operations International Limited and Apple Inc., as parent companies. Authorite de la Concurrence

Privacy advocate Cory Doctorow, author and special advisor at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), has been sharply critical of Apple’s approach to privacy.

Apple has a tactical commitment to your privacy, not a moral one. When it comes down to guarding your privacy or losing access to Chinese markets and manufacturing, your privacy is jettisoned without a second thought. Cory Doctorow - Former European director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation

Doctorow recently elaborated on this perspective in a blog post that includes numerous specific examples.

Last week, Meta announced that they would begin to use user interactions with its AI products to sell targeted adverts. Meta is not doing this in the UK, EU or South Korea where privacy laws prevent this type of data collection. Note, Apple’s privacy rules for iOS, which are inconsistently and weakly applied, are not preventing this data collection. This is a striking reminder, that once again, regardless of Apple’s talking points, privacy laws, not Apple’s review process, is the more effective protector of end users.

Meta announced on Wednesday that data collected from user interactions with its AI products will soon be used to sell targeted ads across its social media platforms.

The company will update its privacy policy by December 16 to reflect the change and will notify users in the coming days. The new policy applies globally, except for users in South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the European Union, where privacy laws prevent this type of data collection. Maxwell Zeff - TechCrunch

Apple Intelligence

Apple has recently threatened to withhold several features from EU consumers, including its new “Apple Intelligence” suite, in response to the Digital Markets Act (DMA). The EU should not take these threats seriously.

Apple is highly unlikely to risk harming its bottom line by undermining its lucrative European iPhone sales. EU consumers should be commended for recognizing these tactics for what they are: a calculated attempt by a major tech company to portray competition regulation as harmful to consumers. In reality, Apple’s resistance stems from its desire to avoid interoperability and competition rules that could weaken its long-term strategy of ecosystem lock-in and open the door to fair competition.

With fewer groundbreaking innovations each year, Apple has increasingly relied on pre-announcing ambitious products that are often incomplete or unavailable at launch. This shift has drawn criticism from longtime Apple observers who note the company’s growing disconnect from its once product-driven ethos. As John Gruber of Daring Fireball put it:

The Apple of the Jobs exile years — the Sculley / Spindler / Amelio Apple of 1987–1997 — promoted all sorts of amazing concepts that were no more real than the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park, and promised all sorts of hardware and (especially) software that never saw the light of day. Promoting what you hope to be able to someday ship is way easier and more exciting than promoting what you know is actually ready to ship. [...]

Tim Cook should have already held a meeting like that to address and rectify this Siri and Apple Intelligence debacle. If such a meeting hasn’t yet occurred or doesn’t happen soon, then, I fear, that’s all she wrote. The ride is over. When mediocrity, excuses, and bullshit take root, they take over. A culture of excellence, accountability, and integrity cannot abide the acceptance of any of those things, and will quickly collapse upon itself with the acceptance of all three. John Gruber - Daring Fireball

(emphasis added)

The problem for Apple, however, is not simply that “Apple Intelligence” is unavailable in the EU, it’s that it doesn’t work very well. Despite being marketed as the headline feature of the iPhone 16, the system has failed to meet even modest expectations.

In fact, Apple is now being sued by consumers who say Apple tricked them into buying phones for a feature that didn’t exist:

The complaints, consolidated in the US District Court for the Northern District of California, alleged that Apple tricked consumers into buying new iPhone 16s by touting state-of-the-art artificial intelligence features the company knew it couldn’t deliver.

The company promoted new features under its “Apple Intelligence” suite to be unveiled with the iPhone 16 line, including an enhanced Siri function that was the centerpiece of Apple’s annual Worldwide Developers Conference in June 2024, the complaint said. Shweta Watwe - Bloomberg Law

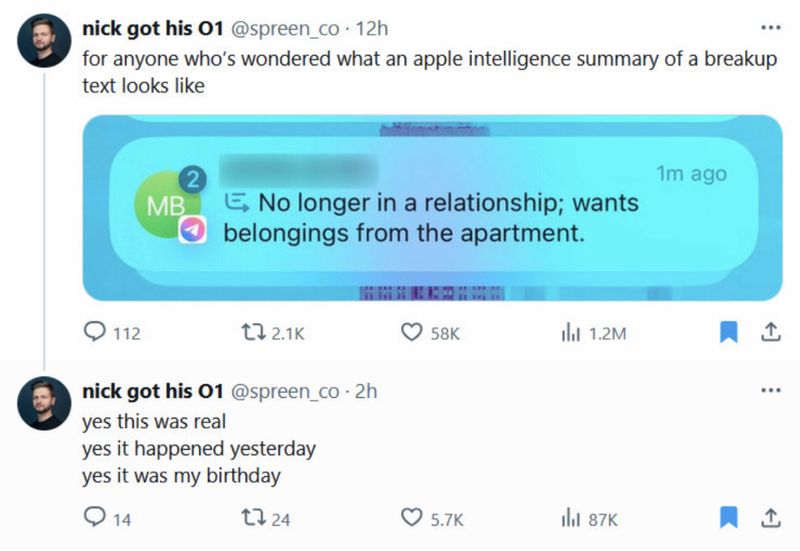

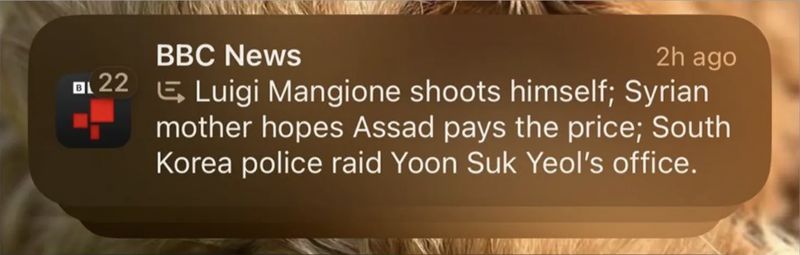

Beyond legal troubles, Apple Intelligence has also failed spectacularly on several occasions for features meant to summarize news or notifications.

For example, this story where a man received an AI summary notification of a breakup: “No longer in a relationship; wants belongings from the apartment.”

Or more disturbingly in December 2024, Apple’s AI-powered summary falsely made it appear that BBC News had published an article claiming Mangione, the man accused of the murder of healthcare insurance CEO Brian Thompson in New York, had shot himself. He had not.

The EU thankfully was spared these issues due to Apple deciding not to roll out the product in the region.

This string of missteps has drawn sharp criticism from prominent Apple commentators such as Stewart Alsop, MG Siegler, and Marques Brownlee, with some even calling for Tim Cook to step down or at least announce his successor.

EU policymakers should not fear being left behind without Apple’s newest features and services. What should truly concern EU policy makers is that European consumers and developers remain deprived of third-party innovations, apps and services that Apple continues to block from competing fairly on iOS.

The DMA already provides the tools to fix this. Interoperability is the key. What’s needed now is the determination, resources, and political will to enforce it fully.