Share and join the conversation: X/Twitter, Mastodon, LinkedIn and Bluesky.

Web platform (noun): The technology and tools that let websites and web apps work in your browser.

Key Takeaways (TL;DR)

DOJ wants to force Google to sell Chrome and ban search engine revenue share deals with other browser vendors, resulting in a 70% drop in funding for the web platform.

Progress in new web features could stagnate, and the performance, stability of the existing web could deteriorate, risking its viability.

We estimate ending the Apple-Google deal alone could cut Google’s U.S. search share by 23–32%.

Mozilla could go bankrupt, killing Gecko, one of just 3 major browser engines.

Most Chromium-based browsers rely on Google’s funding to function.

The open web supports trillions in economic value and it’s mostly free to use.

The impact will likely fall hardest on small U.S. e-commerce businesses that depend on the open web to compete.

DOJ can reduce Google’s market share below 50% without destroying browser funding.

New Chrome owner is likely to gut web platform funding to hit short-term profit targets.

If the web is dealt this critical blow, users will be pushed over to Apple’s and Google’s closed ecosystems.

You can also download the PDF version [10.9 MB]

Introduction

In late 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), in conjunction with state attorneys general representing 11 states, brought a landmark antitrust case against Google for unlawfully maintaining a monopoly in the general search engine market. In August 2024, Judge Mehta ruled in favor of the DOJ, declaring unequivocally that “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly”.

We believe this ruling was correct, necessary, and that the DOJ’s case is compelling.

The DOJ has proposed an extensive list of remedies aimed at restoring competitive conditions in the market for general search engines in the United States. The vast majority of the numerous remedies the DOJ has proposed seem reasonable and proportionate. But amidst this sweeping package, two key remedies in particular have the potential to cause significant, severe, and sustained collateral damage to the web platform.

They are:

A total ban on search engine revenue sharing deals between browser vendors and Google.

A forced sale of Chrome by Google (and barring Google from re-entering the browser market for 10 years).

We fully understand the rationale behind prohibiting search engine revenue-sharing agreements and support the DOJ's decision to cancel the Apple-Google search deal, which undermines iOS browser competition and, with a possibly 98.5% profit margin, channels only a minimal share of its value into web platform development. However, we are concerned about the unintended consequences this approach may have on smaller browsers, particularly Mozilla. Stripping Google of, at most, an additional 1.15%, and likely only 0.74%, of U.S. search traffic does not justify the risk of bankrupting a key contributor to the open web ecosystem.

Mozilla plays a uniquely valuable role in the internet ecosystem as a non-profit committed to an open, secure, and user-centric internet. Despite its modest market share, Mozilla has a large influence on web standards, holding equal footing with Google and Apple in governance bodies like the W3C TAG. Mozilla also maintains its own independent engine, Gecko, which ensures diversity in browser implementations. Gecko is one of only three engines left in major usage. Mozilla frequently serves as a crucial third implementor voice in standards discussions, offering a non-profit perspective grounded in the public interest. Removing Mozilla from this equation would do far more harm to the long-term health of the web than any marginal competitive benefit from eliminating its Google deal, especially when other remedies are already projected to push Google’s market share below 50% and the drop in Google’s share from this remedy is so negligible.

Even more concerning is the likely collapse in web platform investment if Google is forced to sell Chrome. Google currently funds an estimated 90% of Chromium development. Chromium is the open-source project that powers a number of browsers including Chrome, Edge, Opera, Samsung Internet, Vivaldi, Brave, and many other smaller browsers. If Google is forced to divest Chrome and can no longer fund the project, that investment may evaporate overnight. Smaller browsers do not have the resources to fill that gap. In total, this could result in an estimated 70% drop in funding for the web platform, a catastrophic blow to the ongoing evolution of the web. Progress in new web features could stagnate, and the performance and stability of the web platform will deteriorate.

This in turn would harm the ability of the web to compete with the mobile app store duopoly of Apple and Google, directly undercutting the DOJ’s case against Apple, and threatening recent progress by UK and EU regulators to improve competition between browsers and between web apps and native apps. Critical efforts to port both Chromium and Gecko to iOS could be abandoned entirely.

What makes the web unique is that it is not built to trap users in closed ecosystems. It is the world’s only truly open and interoperable platform, one that requires no contracts with OS gatekeepers, no revenue cuts to intermediaries, and no permission from dominant platform owners. Anyone can create a website or web app without needing approval from Apple, Google, or any other gatekeeper. There are no lock-in mechanisms designed to keep users tethered to a single vendor’s hardware or services. Users can switch browsers, change devices, or move between ecosystems without losing access to their data, tools, or digital lives. That level of freedom and portability simply does not exist in app store-controlled environments, where every update, transaction, and user interaction can be subject to control, censorship, or a mandatory financial cut. The web’s architecture prioritizes user agency, developer freedom, and cross-platform compatibility. In short, the web is the antidote to operating system platform monopolies.

Building an app, convincing users to install, and then to engage with it presents an incredibly high bar and massive friction. Major brands with established fans can achieve escape velocity, but the millions of SMBs trying to make their first sale? They stand no chance. They're operating on razor-thin margins, and the online store is the primary and predominant channel of choice because it is a one-tap destination for the potential buyer. It is also the only channel that gives them full creative control, one-tap open and permissionless discovery, and direct relationship with the customer. Continued success of the open web platform is essential to the success of all merchants, and existential for most SMBs.

Ilya Grigorik - Distinguished Engineer at Shopify

Perhaps even more troubling, the fallout wouldn’t be limited to mobile. This could also harm the web on a platform it is already dominant: desktop. Over 70% of user time on desktop is spent in the browser, only possible thanks to the vast multi-year investment in web technologies over the last decade.

In trying to solve one monopoly problem, the DOJ could unintentionally harm the open web ecosystem, a sector worth trillions to the U.S. economy. Web technologies are also used in a vast array of native apps and power the code run on servers of the most high traffic applications in the world. From WebRTC to the V8 JavaScript engine that powers Node.js, the impact of this more than a billion-dollar annual investment in the web is staggering. No one truly knows what the impact of cutting this investment off will be. Certainly, all the code already written will not disappear, but new feature development will stall and severe bugs and security vulnerabilities are bound to become more frequent. This will reduce the stability that developers so desperately need, pushing them towards closed ecosystems.

Given the sheer scale of the web’s usage, its role underpinning the multi-trillion dollar digital economy, the rapid pace of innovation that would be disrupted, and the weak competition on alternative platforms (such as the mobile app stores), it is easy to predict that the resulting damage to US companies and consumers will be in the billions per year.

We believe the DOJ can avoid this outcome. We are optimistic that with targeted adjustments, the DOJ can achieve its goal of breaking Google’s monopoly while safeguarding the web platform's funding and the vast benefits it brings so many US consumers and businesses every year, for free. In fact, we believe that the DOJ could increase both funding and browser competition with adjustments to their existing remedies.

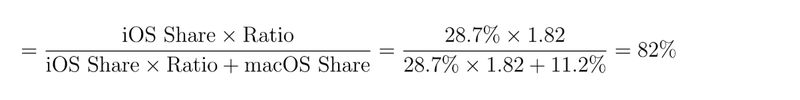

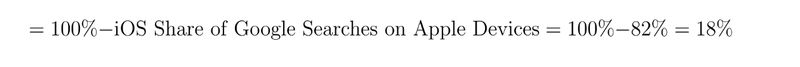

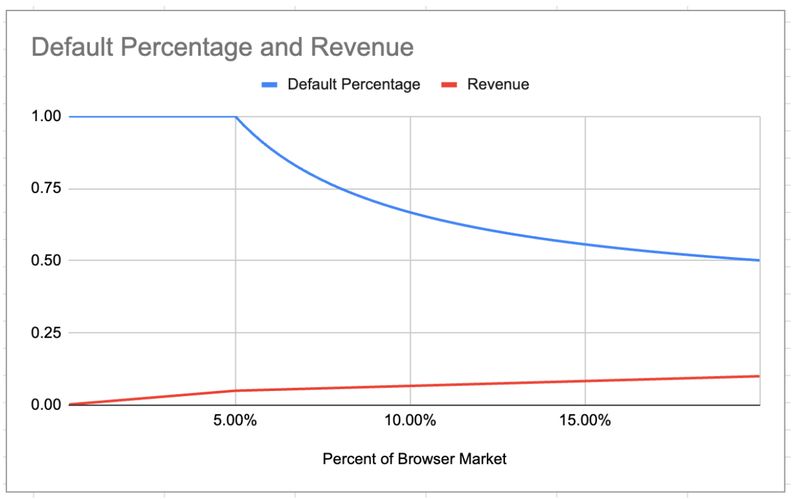

Given that just one of the DOJ’s remedies, canceling the Apple-Google search deal, will by our estimate reduce Google’s U.S. search market share by approximately 21.8% to 30.2%, there is a strong argument that the DOJ can succeed without resorting to remedies that risk gutting web platform funding.

We propose the following six potential targeted changes:

Cap Google’s default search deals to 50% per browser, excluding Apple, whose contract should be canceled entirely.

Mandate 90% reinvestment of Google search revenues into web platform and browser development.

Restructure Chrome as an independent subsidiary within Alphabet.

Enforce transparency and fair revenue share terms across all search deals.

Conservatively, we estimate these adjusted remedies would reduce Google’s U.S. search market share to below 50%, the threshold for presumed monopoly power. Critically, though, rather than collapsing platform funding, these adjusted remedies would likely increase web platform investment by 150%, creating a healthier, more competitive, and more innovative internet ecosystem.

Since the primary justification for these remedies is to prevent actions that would inadvertently dismantle the funding that sustains the web platform, it is both logical and essential that they include concrete safeguards to ensure that goal is actually met. For this reason, we have proposed measures such as minimum reinvestment requirements for any revenue derived from Google search deals, so that these remedies not only avoid harm, but actively support the long-term health of the web platform.

Our goal is not to weaken the DOJ’s case or shield Google. The anticompetitive behavior must be addressed, but the remedies must not destroy the very ecosystem that Google itself indexes.

The DOJ’s case has the potential to unlock vast benefits, not just for search, but for the web itself. We urge both the DOJ and the court to carefully consider the ramifications of their remedies and adjust them where needed. The web platform is too important, and too valuable, to become unnecessary collateral damage in the fight to rein in Google’s search dominance.

2. About Open Web Advocacy

Open Web Advocacy (OWA) is an independent non-profit dedicated to promoting fair competition in both browsers and web apps. We receive no funding from browser vendors, search engine providers, or any companies involved in this case, nor do we advocate on their behalf. Our work is focused entirely on defending the interests of consumers, developers, and the open web.

Our interest in this case is driven by concern over the potential unintended consequences of some of the DOJ’s proposed remedies, and the broader impact these measures could have on the health of the web and the millions of developers and billions of consumers who rely upon it.

3. Table of Contents

Table of Contents

4. Quick Primer on the DOJ’s Case

5. Did the DOJ Deserve to Win?

6. What Remedies Are on the Table?

6.1. Proposed Remedies and Their Potential Unintended Consequences

7. The Problem with Canceling Deals with Small Browsers

8. The Issue with Forcing Google to Sell Chrome

9. The Browser Engine Landscape

9.3.5. Smaller Browser Vendors

10. Native App Closed Gardens vs The Open Web

11.3.1. Core/Major Chromium Technologies

11.3.2. Graphics, Rendering and Visual

11.3.3. Networking and Communication

11.3.4. Developer Tools and Debugging

11.3.5. Security, Safety, and Privacy

11.3.7. Collaboration with Standards Bodies

11.4.8. Communication – WebRTC

11.4.9. Graphics – Skia & Dawn

11.4.10. Video & Image Codecs – AV1, VP9, WebP

12. What Does It Cost to Develop and Maintain the Web Platform?

12.1. How Much Does Blink/Chromium Cost?

12.2. How Much Does WebKit Cost?

12.3. What About the Other Chromium Browsers?

12.4. How Much Does Gecko Cost?

12.5. Is $400 Million a Year Enough to Fund Gecko and Firefox?

14. What’s at Risk for the Open Web?

15. Estimating the Impact on Web Platform Funding

15.5. Smaller Chromium Browser Vendors

15.7. Other Non-Browser Companies

15.9. What could the Total Impact Be?

16. Could this case be good for the Web?

17. Should the Apple Google Search Deal be Banned?

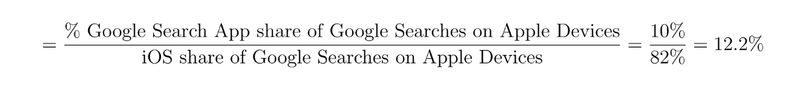

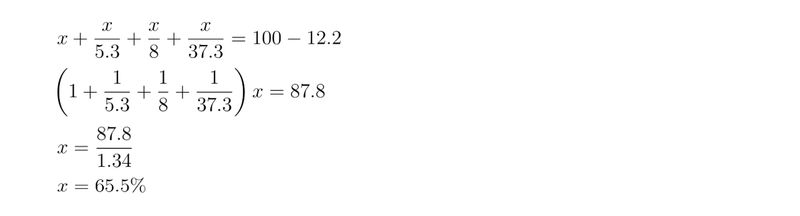

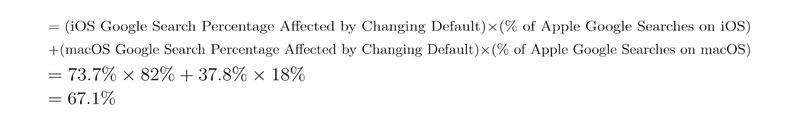

17.1. Breakdown of Apple-Google Search Deal

17.2. How much share would Google lose if Apple changed the Default Search Engine?

17.3. Impact of the Syndication Remedy

17.4. Apple’s Response to the Search Deal

17.5. Google’s Response to the Search Deal

17.6. Harms and Benefits from Canceling the Apple - Google Search Deal

17.6.2. Increases Apple’s Revenue

17.6.3. The Benefits of Canceling the Apple-Google Search Deal

17.7. Should the Deal be Canceled?

17.8. What does this mean for the DOJs other remedies?

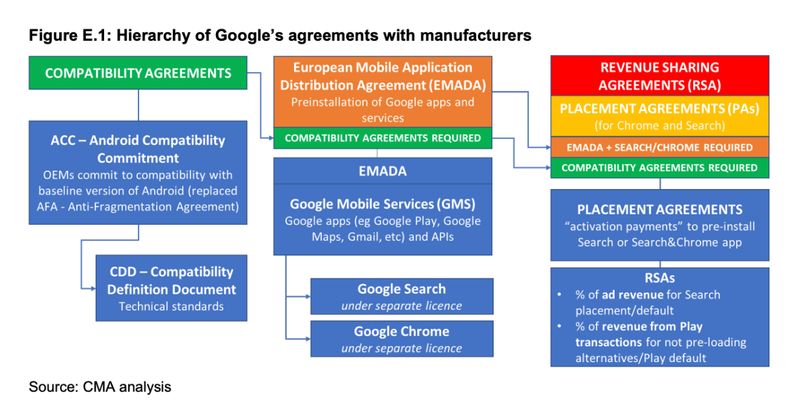

18. Should the Google Android Placement and Bundling Deals be Banned?

18.1. The 11 Core GMS Applications

18.3. Should Google’s OEM Deals Be Allowed?

19. Should all Search Engine Default Placement Deals be Banned?

20. Fixing the Problem Without Breaking the Web

20.1. Protecting the Web Platform’s Funding

20.2. Preventing Browser Market Consolidation

21. Challenges for those Arguing for Chrome Divestment

22. Challenges for those Arguing for Banning Search Engine Deals with Small Browsers

23. Potential Alternative Remedies

23.1. Cap Default Search Deals at 50%

23.2. Allow Exceptions for Small Browsers

23.3. Require Reinvestment of Search Revenue into Browsers and the Web Platform

23.4. Transfer Chrome to a Non-Profit

23.5. Allow Chrome’s Sale with Minimum Platform Investment Conditions

23.6. Move Chrome from Google to Alphabet

23.7. Cap Chrome’s Search Defaults to Google at 50%

23.8. Transparency and Uniform Revenue Share Requirement

23.9. Guarantee that Google Is Not Barred from Investing in Chromium

24.1.1. Preserve and Implement Majority of the DOJ's Existing Remedies

24.1.2. Terminate the Apple-Google Search Agreement

24.1.3. Eliminate OEM Placement, Revenue Sharing, Placement and Bundling Agreements

24.1.4. Permit Browser Search Default Deals up to 50% Market Share, Excluding Apple

24.1.5. Require Reinvestment of Search Revenue into Browser and Web Platform Development

24.1.6. Carve-Out for Smaller Browsers

24.1.7. Move Chrome from Google to Alphabet

24.1.8. Conditions on Search Deals

24.2. Estimated Impact on Web Funding

24.2.5. Smaller Browser Vendors

24.2.6. Other Non-Browser Companies

24.2.7. Estimated Total Impact on Web Platform Investment

24.3. Estimated Impact of the Package on Google's Search Engine Market Share

24.3.1. Safari, Spotlight and Siri

4. Quick Primer on the DOJ’s Case

The federal antitrust case United States v. Google LLC was filed by the Department of Justice (DOJ) on October 20, 2020. The DOJ alleged that Google violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by unlawfully monopolizing the search engine market.

Google has entered into a series of exclusionary agreements that collectively lock up the primary avenues through which users access search engines, and thus the internet, by requiring that Google be set as the preset default general search engine on billions of mobile devices and computers worldwide and, in many cases, prohibiting preinstallation of a competitor. DOJ - Statement on Issuing Complaint

This lawsuit is part of a broader wave of antitrust actions by the DOJ and FTC against major tech companies, including Meta, Amazon, Apple, and another separate case targeting Google’s advertising technology business.

On August 5, 2024, the DOJ won the suit when Judge Mehta ruled that Google held a monopoly in the general search services market, and had illegally used that position to maintain its monopoly.

After having carefully considered and weighed the witness testimony and evidence, the court reaches the following conclusion: Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly. Judge Mehta - Judgement

Following the ruling, on November 20, 2024, the DOJ released an initial proposed final judgment outlining potential remedies to address Google’s monopolistic practices. The document is extensive and details numerous overlapping remedies, which will be discussed in more detail later.

The DOJ submitted its updated remedies on March 7, 2025, which coincidentally marked the one-year anniversary of the EU’s Digital Markets Act coming into force.

Apple sought to join the proceedings but was decisively rejected on the grounds that it had waited nearly four years to make the request. The court also found that Google was sufficiently positioned to represent Apple’s interests in the case. However, Apple was granted permission to submit an amicus brief, a filing by a non-party, intended to offer additional legal arguments or context for the court to consider.

A trial on these remedies started this monday, with a final ruling by Judge Mehta anticipated by August 2025.

However, legal experts predict the case will be appealed, likely delaying the implementation of any remedies further.

5. Did the DOJ Deserve to Win?

The core argument in the case is that Google leveraged its vast profits and dominant market position in the search engine industry to establish a series of overlapping contractual arrangements, creating significant barriers for new competitors to enter the market.

Although we are not legal experts or scholars, as technical professionals in the industry, we find the DOJ’s case compelling. In our view, the ruling was well justified. While we might disagree with some individual points raised during the proceedings, it is evident that Google’s practices have made it exceptionally challenging for competitors to gain a foothold in the search engine market. In our conversations with software engineers and academics, few questioned the fundamental validity of the DOJ’s case.

6. What Remedies Are on the Table?

The list of remedies that the DOJ has proposed is extensive, and it is essential to at least skim through it to grasp the scope and scale of the proposed measures. Many of the remedies are profoundly impactful on their own. While some may not be adopted by the court, the DOJ appears to be advocating for the implementation of every remedy listed, not just a select few.

These have been abbreviated and rewritten for the purposes of readability and “brevity” but you can read the originals and updated remedies. In some cases remedies have been split for readability purposes. Finally you may also be interested in this justification document submitted at the same time by the DOJ.

Google is prohibited from compensating or incentivizing any third party to block entry into the General Search Engine market or the Search Text Ad market.

Google is prohibited from compensating or incentivizing any third party to give preferential treatment to Google Search or any Google Search Access Point (e.g., Google Search App, Chrome) over its competitors.

Google is prohibited from compensating or incentivizing any third party to set or maintain any General Search Engine as the default in a new or existing Search Access Point.

Google is prohibited from compensating or incentivizing any third party to discourage the use of competing General Search Engines.

Google is prohibited from compensating or incentivizing any third party for pre-installation, positioning, or setting any Search Access Point as the default.

Google is prohibited from compensating or incentivizing Apple to refrain from entering the General Search Engine or Search Text Ad markets, effectively nullifying the Google-Apple search agreement and broadly barring any future similar arrangements.

Google is not allowed to contract with publishers to licence data in any way which provides Google exclusivity or prevents the publisher from making the same data available to any other General Search Engine or AI product.

Google is not allowed to condition access to the Play Store or any other Google product on a distribution agreement for a GSE, Search Access Point, or Choice Screen. Similarly they may not condition it on not distributing a Competitor’s product or service.

Google may not bundle or tie any Google Search Engine or Search Access Point by, for example, licensing a product to a distributor and including a General Search Engine or Search Access Point for free.

Google may not pay any distributor any amount that is calculated based on the usage of or revenue generated by any Google Search Engine. This is essentially a ban on all revenue sharing agreements that Google currently has.

Google must (within 6 months) sell any investment it has in any company that controls a Search Access Point, an AI Product or similar technologies that are potential entrants into the General Search Engine or Search Text Ads market or could be reasonably anticipated competitive threats to General Search Engines. Google must immediately refrain from taking any action that could discourage or disincentivize from developing products that would compete with or disrupt Google's General Search Engine or Search Text Ads.

Google must not without prior written consent of the United States acquire any interest in, invest in, partner with, expand the scope of an existing joint venture of any company that that competes with Google in the GSE or Search Text Ads markets or any company that controls a Search Access Point or query-based AI Product.

Google must promptly and fully divest Chrome, to a buyer approved by the Plaintiffs in their sole discretion subject to terms that the Court and Plaintiffs approve.

Google may not release any other Google Browser during the term of this Final Judgment (the next 10 years) absent approval by the Court.

Google must not use any Google-owned asset (including any software, website, device, service, dataset, algorithm, or app) to self-preference Google’s GSE, Search Text Ads, or AI Products. The section provides a long list of examples.

Google must not use any Google-owned asset (including any software, website, device, service, dataset, algorithm, or app) to self-preference Google’s GSE, Search Text Ads, or AI Products. The section provides a long list of examples.

Google must not use any Google-owned asset (including any software, website, device, service, dataset, algorithm, or app) to undermine or lessen the ability of a user to discover a rival GSE or of an advertiser to discover or shift its Search Text Ad spending to a rival Search Text Ads provider. The section provides a long list of examples.

Google must not use any Google-owned asset (including any software, website, device, service, dataset, algorithm, or app) to undermine or lessen the ability of a user to discover a rival GSE or of an advertiser to discover or shift its Search Text Ad spending to a rival Search Text Ads provider. The section provides a long list of examples.

If the remedies fail to restore competition or if Google circumvents them, the Court may order additional measures, including divesting Android (and the Google Play Store). If the DOJ proves insufficient competition persists, Google must divest Android (and the Google Play Store) unless it proves that its ownership did not substantially hinder competition.

Google must provide its Search Index to Qualified Competitors at marginal cost, ensuring equal access for both Qualified Competitors and Google.

Google must include content from all its owned or operated platforms (e.g., YouTube) in the Search Index it shares.

Google must ensure the shared Search Index has the same latency and reliability as Google's own access.

Google cannot use or retain data that cannot be shared with Qualified Competitors due to privacy or security concerns.

Google must provide publishers, websites, and content creators a simple way to selectively opt-out of having the content of their web pages or domains used in search indexing, AI training, AI tools, or AI-generated content on Search Engine Result Pages. This opt-out applies to Google and all Search Index users, must be user-specific, and includes Google-owned platforms like YouTube, with no retaliation allowed.

Google must provide Qualified Competitors with free, non-discriminatory access to User-side Data while protecting privacy and security. Google has six months to implement the necessary technology, and competitors can choose real-time or daily access via API, data firehose, or other suitable mechanisms Google uses in its own search engine.

Google must allow Qualified Competitors to submit synthetic queries for free. Competitors may log and use the results, including ads and Search Engine Page Result content. The maximum number of allowable synthetic queries will be determined by the Plaintiffs in consultation with the Technical Committee.

Google must provide Qualified Competitors with free, non-discriminatory access to Ads Data while protecting privacy and security. Google has six months to implement the necessary technology, and competitors can choose real-time or daily access via API, data firehose, or other suitable mechanisms Google uses in its own search engine.

Google must offer Qualified Competitors a 10-year syndication license at marginal cost, providing all non-advertising components of its General Search Engine (organic results, Search Features, Ranking Signals, and query understanding) to enable licensees to display Search Engine Page Result, understand ranking logic, and query modifications. The license must be non-discriminatory, unrestricted in use or display, and interoperable with Search Access Points and AI products, while allowing Google to protect its brand, reputation, and security. This only requires Google to provide syndication for queries that originate in the United States. The licence will have the following required features:

a) Google must deliver syndicated content via an API with latency and reliability equivalent to its own Search Engine Result Page.

b) Syndication access will start broadly and decline over 10 years, encouraging licensees to build independent search capabilities, with scope set by Plaintiffs and the Technical Committee.

c) Google may not consent to licensees exceeding syndication limits set by Plaintiffs, and licensees must submit to the Technical Committee audits of syndication frequency.

- Google must provide Qualified Competitors a 1-year non-discriminatory license for all components of its Search Text Ads, including any assets, extensions, or similar Search Text Ad variations that appear on Google’s Search Engine Result Page or available through Google’s AdSense for Search. Google must share all related Ads Data without restricting use, display, or interoperability with Search Access Points or AI products, while allowing reasonable protections for its brand, reputation, and security. This only requires Google to provide syndication for queries that originate in the United States. Additionally:

a) Google must provide syndicated content via an API with latency and reliability equivalent to its own Search Text Ads on Search Engine Result Pages.

b) Licensees may request syndicated ads for up to 25% of U.S.-originating queries, with no exceptions allowed. Licensees must also submit syndication frequency audits to the Technical Committee.

For existing Google syndication agreements or new contracts with third parties outside Qualified Competitors Google must:

a) Google must allow Qualified Competitor to terminate its existing agreement in favor of the new rules.

b) Google must follow the new rules either within two years of the Effective Date or when any current syndication contract ends, whichever comes first.

For any current or future agreements where Google licenses or syndicates search or search ads products to a competitor, Google cannot:

a) Restrict how competitors use, display, or integrate these products with Search Access Points or AI tools, but Google can take reasonable steps to protect its brand, reputation, and security. Competitors can decide which queries or syndication components to use or display however they want.

b) Keep or use data from syndicated queries or information from competitors for its own products or services.

Google must provide advertisers with detailed data for each Search Text Ad served or clicked from the preceding 18 months. This includes the query, keyword trigger, match type, CPC, SERP position, LTV, and other metrics to evaluate ad performance. Data must be accessible via an API for real-time downloads, reporting, and analysis, as well as through auto-generated monthly summaries in the Google Ads interface.

Google must provide advertisers with a keyword matching option that ensures ads enter the auction only when a query exactly matches the chosen keyword, with no variations. This option must also apply to negative keywords.

Google must allow advertisers to export all their ad and campaign data, including placement and performance metrics, in real time through an interface or API.

Each month, Google must report to the Technical Committee and DOJ all changes to its Search Text Ads auction, include public disclosures or explain why none were made, and identify any material changes.

Google must not pay Distributors for default settings, placement, or preinstallation of a General Search Engine or Search Access Point on non-Apple, third-party devices. Google cannot interfere with the ability of devices or preinstalled Search Access Points to default to or work with non-Google General Search Engine or competitors. For preinstalled Google Search Access Points under prior agreements, Google must offer Distributors the option to display a Choice Screen to users which currently have Google as the default General Search Engine. Google must pay a fixed monthly amount for each such device, based on the average payments made in the past year for the device lifetime or one year, whichever is shorter. Chrome is considered a Google Search Access Point until divested.

Google must not pay any Distributor for any form of default, placement, or preinstallation distribution (including choice screens) related to making any General Search Engine a default within a new or existing Search Access Point.

Google must not preinstall any Search Access Point on any new Google Device.

Google must not hinder the ability of third-party Search Access Point to be set as default or interoperate with non-Google Search Engines or other competitive entrants.

For existing Search Access Point preinstalled on an existing Google Device before the date of entry of this Final Judgment, Google must implement a Choice Screen.

Google must display a Choice Screen on all Google Browsers where the user hasn't affirmatively set a default General Search Engine, including via settings.

Google must disclose each Choice Screens, related distribution agreements, and implementation plans to Plaintiffs and the Technical Committee at least 60 days before user display. The Choice Screen must offer a clear, unbiased selection between competitors, be accessible, user-friendly, and minimize choice friction based on user behavior data. After consulting a behavioral scientist, the Technical Committee will assess compliance and report to Plaintiffs, who must approve any Choice Screen under this Final Judgment.

A five-member Technical Committee (TC) will be appointed to monitor Google’s compliance with the Final Judgment, ensuring fairness and preventing anti-competitive behavior. TC members must be experts, free from conflicts of interest, and will have access to Google's systems, source code, documents, facilities, and personnel to enforce compliance. The TC will report regularly to Plaintiffs, handle complaints, recommend modifications, and operate with Google-funded resources under strict confidentiality agreements. This section of the proposed final judgement is quite extensive on the powers of the technical committee.

Google will appoint a compliance officer who among other duties will distribute a copy of the final judgement to ALL google employees and have them annually certify that they have read, will abide by its terms and understand that failure to do so may result in a finding of contempt of court. This includes appropriate training for all Google employees on how to comply with this judgement.

Google must not retaliate against anyone for competing with its GSE or Search Ads, filing complaints, participating in legal proceedings, or exercising rights under this Final Judgment.

Google is prohibited from enforcing or entering contracts that violate this Final Judgment. It must not replicate banned anti-competitive behavior, evade obligations, or undermine the Judgment’s purpose. If found liable for antitrust violations in federal court, structural relief may be automatically ordered. These provisions apply globally to all Google conduct and contracts.

If after 5 years, Google has complied with all provisions and its competitors combined market share is greater than 50% in the US General Search Engine market then Google may petition the court to terminate this judgement.

6.1. Proposed Remedies and Their Potential Unintended Consequences

Out of the above quite substantial list, two remedies stand out above all others in terms of their impact on the web:

A total ban on deals with Google that set search engine defaults or that share revenue with search engine entry points.

Forcing Google to sell Chrome and banning Google from re-entering the browser market for 10 years.

While we fully understand the intent behind these remedies, we are concerned that the DOJ has not fully considered or appreciated the profound ramifications these remedies will have on the adjacent browser and web software market including:

Bankrupting or shrinking the share of smaller browsers.

Consolidating power in the browser market in even fewer hands.

Plummeting investment in the Web, thus strengthening the non-interoperable app store model on mobile.

7. The Problem with Canceling Deals with Small Browsers

Google has agreements with several browser vendors to set Google as the default search engine for users who have not previously made a manual choice. In return, Google shares a portion of the revenue it earns from searches performed through those browsers.

The most prominent of these deals is with Apple, which receives an astronomical $20 billion per year from Google. This deal is also the most problematic as we estimate only a minute percentage of it (likely less than 3%) is invested back in Safari/WebKit, leaving the remainder as pure profit.

Google also maintains revenue-sharing agreements with several smaller browser vendors, including Mozilla. These browsers rely heavily on this funding to sustain operations. Google is estimated to pay Mozilla approximately $410-420 million per year, though public figures for its deals with other vendors are not available. While these browsers collectively represent only a small share of the market, they play a disproportionately important role in maintaining competition within the browser ecosystem. However, according to the court judgment, they account for just 1.15% of search queries in the United States.

Expanding the presence of smaller browsers is vital. A greater number of competitors leads to stronger and fiercer competition, pushing larger players to innovate and improve. It is essential that any remedies to the current market dynamics do not further reduce the number of players in the browser ecosystem.

Smaller browsers are our best hope for cultivating a more competitive market in the future. Ideally, in 5 to 10 years, a more balanced search engine landscape would lead to increased competition for placement deals, driving higher revenues for smaller browsers. This additional funding could help them grow and gain market share.

In the short term, however, blocking these funding arrangements could jeopardize the financial stability of smaller browser vendors. While they might seek deals with Bing or other search engines, those arrangements would likely yield lower payments, as Bing would only need to outbid smaller rivals and not Google, further reducing the resources available to these browsers.

Mozilla, in particular, is at significant risk due to the high costs associated with maintaining and advancing its Gecko browser engine. Losing Mozilla would be a major blow to competition, as it represents a unique alternative in the market. In contrast, larger browsers like Microsoft Edge and Apple Safari are likely to survive, supported by their parent companies’ vast resources and strategic interests. However, a market reduced to three dominant players, including Safari which operates solely on Apple’s platforms, would critically undermine competition.

We believe that blocking smaller players from making search deals with Google is unjustified given the broader harm this would cause to the browser market. The potential benefits in the search engine market are minimal compared to the significant blow to browser competition. Ensuring the survival and growth of smaller browsers is key to a healthier, more competitive ecosystem.

Any remedy that would significantly impact the finances of the smaller browsers should be backed by detailed arguments as to why it will not cause the exit of these smaller players and consolidation in the hands of a few tech giants.

During the case, evidence showed that Mozilla reinvested much of the revenue from its Google search deal into Firefox and Gecko. However, its 3% market share was deemed too small to be relevant to significantly benefit the public.

This reasoning is flawed. If Mozilla’s market share is considered negligible, then their share of Google’s search payments, only 1.6% of what Google pays browsers and OEMs, should also be seen as insignificant in the broader context. It is inconsistent to argue that one metric matters while dismissing the other.

That is, the questions that should be asked are:

Do payments to Mozilla and other smaller browsers cause more harm by limiting opportunities for other search engines to enter the market, or do they provide greater benefits by enabling Mozilla’s critical contributions to web standards, browser development, and the maintenance of Gecko, one of the three remaining browser engines?

Given Mozilla’s 3% market share, doesn't its role in hindering other search engines pale in comparison to Google’s other strategies, such as the Apple Search deal, Android OEM placements, revenue-sharing agreements, and defaults in Google’s own browser?

We firmly believe the answer lies in allowing Mozilla and other smaller browsers that rely on Google’s search deals to continue to make them. The DOJ can address Google’s monopoly without crippling or mortally wounding Mozilla, an already struggling but vital player, or undermining the broader ecosystem of smaller browsers.

8. The Issue with Forcing Google to Sell Chrome

The DOJ has proposed that Google be required to sell Chrome and banned from re-entering the browser market for 10 years, which raises several important concerns.

A key question is: Who would buy Chrome, and once purchased, what would its revenue source be?

The proposed remedies prohibit any search deal with Google, including partial agreements, leaving its financial viability uncertain. While this new entity would be free to make deals with other search engines such as Bing, would this be enough to cover costs, and would these search engine providers feel pressure to bid sufficiently large sums?

We are particularly worried about the possibility of Chrome being acquired by an entity that does not value the open web, or worse, is actively opposed to it.

Another concern is whether a new owner would continue funneling the necessary investment, which we estimate at around $1 billion annually, into maintaining and advancing the platform. The web platform relies on a vast body of work that extends far beyond the code in any single browser engine. It includes infrastructure maintenance, security research, standards development, and the efforts of web advocates: individuals and organizations committed to improving the web as a whole. Today, the overwhelming majority of this work is funded either directly or indirectly by Google.

Assuming they find a buyer, that buyer will be scrambling to find a way to make that investment worth it. Will they be choosing to employ people who are just abstractly making the web better? I would think not. Chris Coyer - CSS Tricks

Google itself would have drastically reduced incentive to invest in Chromium, as it would no longer benefit directly from maintaining a browser. Moreover, the risk of another tech giant acquiring Chrome could create a similar antitrust issue down the road. For example, if Microsoft were to regain a dominant share of browsers on Windows, it could mirror the competitive concerns of its antitrust case from 20 years ago. While we support Edge as a minority browser, we remain critical of certain anti-competitive practices Microsoft is currently employing on Windows to increase its browser market share.

A potential disaster scenario emerges if Chrome is acquired by a buyer focused on short-term returns. After investing a substantial amount to acquire the browser, the new owner would face strong incentives to prioritize rapid monetization over long-term investment in the web platform.

Corporate acquirers targeting high-risk, high-reward purchases typically aim for annual returns exceeding 15–20%. With a $20 billion purchase price under discussion, the buyer would be under significant pressure to generate $3–4 billion in annual profit to justify the investment. In that context, it would be entirely rational for them to focus solely on revenue-driving components.

This makes it likely that any investment in a newly acquired browser would be concentrated on user-facing features that grow or maintain market share. Improvements to the underlying web platform, which would benefit all Chromium-based browsers including direct competitors, would likely be deprioritized.

If the acquirer were unable to secure a lucrative search deal with Google (due to a prohibition from the court), the next logical option would be Microsoft’s Bing. However, in a world where Google is not bidding, it's unclear how much Microsoft would be willing, or feel compelled, to pay. Without competitive tension in the bidding process, any resulting deal would likely be far less valuable.

This scenario could leave the acquirer with substantial engineering overhead and no clear path to recover those costs, let alone achieve the level of profitability their investment demands. The financial strain would be even greater if the acquisition were debt-financed, amplifying the risk of falling short.

This could result in drastic cost-cutting measures, including reducing staff to a bare minimum, terminating teams working on new web platform features, and maintaining only a skeleton crew for basic bug fixes and security updates. The new owners could also focus on extracting maximum revenue from search engine providers and other deals while neglecting long-term improvements to Chrome.

Investment in Chromium, both from this new entity and Google, would likely dry up overnight. The resulting stagnation in web development could have lasting repercussions for decades, as the Web falls behind closed, extractive native app ecosystems.

Does it matter if the web platform adds new capabilities? And if it should, which ones? The web is a meta-platform. Like other meta-platforms the web thrives or declines to the extent it can accomplish the lion's share of the things we expect most computers to do.

[...]

There's no technical reason why, with continued investment, meta-platforms can't integrate new features. As the set expands, use cases that were previously the exclusive purview of native (single-OS) apps can transition to the meta-platform, gaining whatever benefits come with its model.

Alex Russell - Program Manager on Microsoft Edge

This would cause immense harm to countless smaller U.S. businesses that depend on a thriving and continuously evolving Web. Ultimately, it would shift power away from the Web, and into the hands of tech giants controlling the alternative.

Most industry experts we have consulted agree that this is, by far, the most likely outcome. There is widespread fear across the industry, particularly among those who rely on the Web, that such a scenario would have devastating and far-reaching consequences for its future.

9. The Browser Engine Landscape

9.1. Browser vs Platform

Browsers are highly sophisticated pieces of software, tasked with far more than simply rendering web pages. They interpret and execute HTML, CSS, and JavaScript; manage memory and isolate processes for stability; enforce critical security mechanisms like sandboxing and same-origin policies; protect users from malicious content; support audio and video playback; handle networking and caching; integrate with various operating system services; synchronize data such as bookmarks and passwords; and offer robust tools for developers, along with numerous other complex functions. Few, if any, engineers fully understand all the functions a modern browser performs.

Conceptually, browsers can be divided into two main components:

The Browser User Interface

This includes all the visible elements users interact with, such as tabs, address bars, bookmarks, and menus. It also manages user actions like navigating between pages or downloading files. Notably, this excludes the main content area where the web page is rendered, which is the responsibility of the browser engine.The Browser Engine

Often considered the "heart" of the browser, the engine is responsible for rendering web pages, running JavaScript, interpreting HTML/CSS, and managing web APIs. It powers the browser platform, which serves as the foundation for web developers and businesses relying on the web as an application platform.

The term "browser platform" refers to the collection of tools, APIs, and capabilities that enable developers to create websites and web apps. It provides essential features like rendering, storage, communication, and graphics capabilities. While the boundaries of the browser platform can sometimes blur with the broader browser architecture, the bulk of it typically resides within the browser engine.

Industry conversations suggest a consistent view among engineers: building a browser involves roughly a 50-50 split (with about a 10% margin) between developing the browser UI and the underlying browser platform. This balance is generally seen among browsers that are the primary maintainers of their own engines, such as Chrome, Firefox, and Safari. However, other browsers, including well-funded ones like Edge, are believed to overwhelmingly focus their efforts on the browser UI, often allocating over 90% of their resources to it, contributing significantly less to the platform layer. While both components are crucial to delivering a seamless experience for users, the browser platform holds particular importance for businesses and developers. It provides the tools they need to create innovative web applications, deliver services, and support their operations.

The significance of the browser platform cannot be overstated, as it forms the backbone of the modern web. Businesses depend on its reliability, security, and functionality to ensure their web applications perform efficiently across all devices and operating systems. Developers rely on its APIs and tools to push the boundaries of what is possible on the web.

The key factors driving the advancement of the web platform are fierce competition among browsers, the substantial funding necessary to maintain and push forward the platform, and a steadfast belief that given the web's unique attributes of openness and interoperability, the web can and should be allowed to compete fairly.

9.2. Browser Engines

Gecko traces its origins to the defunct Netscape Navigator browser. Mozilla began developing Gecko in 1998 after Netscape open-sourced its code. This effort culminated in the release of Firefox 1.0 in 2004, marking the beginning of renewed competition against the then-dominant Internet Explorer from Microsoft.

WebKit originated as a fork of the KHTML browser engine. As a fork WebKit inherited KHTML's LGPL copyleft license and powers Safari and several smaller browsers. Between the mid-2000s and early 2010s, both Google and Apple contributed code and resources to WebKit. However, disagreements over Apple’s management of the project led Google to hard-fork WebKit in 2013, creating its own engine, Blink.

A soft fork refers to maintaining a customized version of a browser engine while continuing to accept upstream patches and improvements from the core project. In contrast, a hard fork involves taking full control of a new codebase, starting from a snapshot copy of the original, and developing it independently.

Blink powers Chrome, Edge, Opera, Samsung Internet, Vivaldi, Brave, and many other smaller browsers. Its popularity stems in part from the open-source project Chromium, which includes not only the Blink engine but also the full surrounding browser UI. This makes it easy for new browser vendors to create a soft-fork of Chromium, whereas with WebKit or Gecko, they would need to develop the entire browser UI themselves.

Other browser engines, such as Trident and Presto, have fallen out of active development. Trident, the engine behind Internet Explorer, was effectively abandoned when Microsoft transitioned its Edge browser to use Chromium in 2018; it had been using a Trident fork called EdgeHTML. Presto, once used by Opera, was similarly retired in 2013 when Opera also switched to Chromium.

9.3. The Browsers

9.3.1. Chrome

Chrome is Google's browser, built on the open-source Blink engine and the Chromium project, both of which Google primarily develops and maintains. Chrome holds a dominant market share, with approximately 86% on Android, 67% on Windows and 55% on macOS. Google also maintains a Chrome-branded WebKit browser on iOS with a 15.6% share.

Google’s motivations for maintaining and investing in Chrome are wide-ranging and deeply tied to its core business interests.

First, Chrome acts as a vital gateway to Google Search. With Google set as the default search engine for all Chrome users, the browser drives substantial search traffic, translating directly into revenue.

Second, as the operator of major web-based services like Gmail, YouTube, and Google Docs, Google has a strong incentive to ensure the underlying web platform remains fast, stable, and feature-rich, allowing these products to deliver a seamless user experience.

Third, Google’s search business depends on access to the open web. By heavily investing in both Chrome and the web platform, Google increases the share of the world’s data that is publicly indexable, enhancing the reach and relevance of its search engine.

Finally, Chrome plays a strategic role in supporting Google’s advertising ecosystem. Search ads, especially in e-commerce, are typically priced on a per-conversion basis. Improving web performance and capabilities leads to higher conversion rates across the web, making Google’s ads more effective and more valuable to advertisers.

9.3.2. Safari

Safari is Apple's browser, powered by the open-source WebKit engine, which Apple primarily develops and maintains. On iOS Safari has an 82.2% share, and holds approximately 37.8% of the browser market on macOS. While WebKit is open-source, Apple has unilateral control over the version and feature set of the WebKit that is shipped with and is available on iOS.

Safari plays a key role in Apple's branding, positioning itself as a privacy-focused alternative to Chrome.

One significant limitation of Safari as a competitor to Chrome is Apple's decision to restrict Safari's availability to its own platforms, including macOS, iOS, iPadOS, VisionOS, and WatchOS. This exclusivity prevents Safari from being a meaningful competitor in broader browser markets like Windows, Android, and Linux.

Apple has also effectively banned all rival browsers from competing on iOS via their browser engine ban. This lack of competition has diminished Apple's incentive to significantly enhance Safari on iOS beyond what is necessary to maintain its reputation among users. Developers, reliant on supporting iOS, and therefore Safari, often have to find workarounds for various issues.

Apple has a browser monopoly on iOS, which is something Microsoft was never able to achieve with IE

Scott Gilbertson - The Register

because WebKit has literally zero competition on iOS, because Apple doesn’t allow competition, the incentive to make Safari better is much lighter than it could (should) be. Chris Coyier - CSS Tricks

What Gruber conveniently failed to mention is that Apple’s banning of third-party browser engines on iOS is repressing innovation in web apps. Richard MacManus - NewsStack

Additionally, Apple has not provided web apps with the functionality and visibility they need to effectively compete with Apple's own app store while it simultaneously blocks third-parties from providing it via their browser engine ban.

Finally Apple collects $20 billion USD from Google per year, but only reinvests a small fraction of that back into Safari and WebKit, likely less than 3% of the total, leaving the remainder as pure profit. This is estimated at an astonishing 17.5% of Apple's operating profit.

9.3.3. Firefox

Firefox is Mozilla’s browser and is powered by the Gecko engine. While it played a pivotal role in revitalizing competition against Internet Explorer in the mid-2000s, Firefox’s market share has dwindled to single digits in recent years. Mozilla relies primarily on its search engine deal with Google to fund the ongoing development of Firefox and its independent browser engine, Gecko.

Despite its declining market share, Mozilla and Firefox play an outsized and vital role in the development of the web and web standards. However, this role is hindered by insufficient funding. Unlike smaller browsers that can rely on Chromium to reduce costs, Mozilla shoulders the full burden of maintaining an independent browser engine. This independence is vital for web diversity but comes at a steep financial cost.

While Mozilla has undoubtedly made missteps, there is a compelling argument that they have been unfairly prevented from competing on equal terms. On iOS, Apple’s ban on third-party browser engines has effectively barred Firefox from fully competing. Similarly, on Android, Mozilla has faced challenges due to overlapping and restrictive placement deals that favor Chrome. Over the past 15 years, these barriers have likely cost Mozilla billions in search engine revenue. This lost funding could have provided Mozilla with a significantly larger budget to compete head to head on platform via Gecko with Chrome. It would also have given Mozilla more room to make and recover from errors.

9.3.4. Microsoft Edge

Microsoft Edge is built on the Blink engine, utilizing the open-source Chromium project. In 2018, Microsoft transitioned Edge from its proprietary EdgeHTML engine to Chromium/Blink. While Edge is the default browser on Windows, it faces significant competition from Chrome, which remains the dominant browser on the platform.

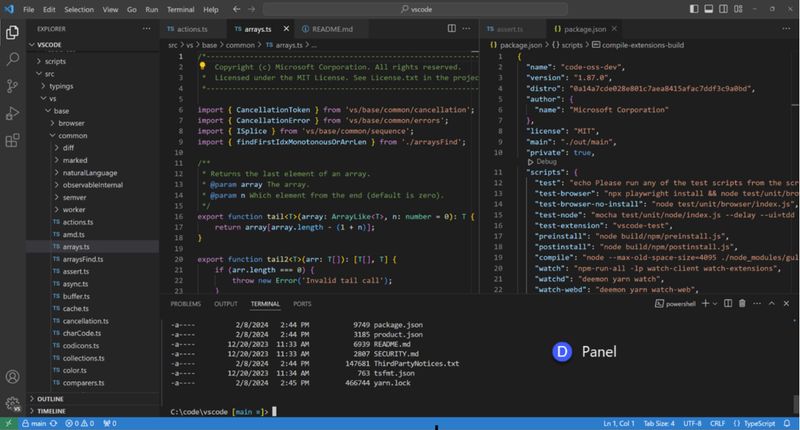

Microsoft is heavily invested in the transition to a more web-centric future. Many of its key applications, such as Teams, Outlook and Visual Studio Code (VSCode), are built using web technologies (e.g., Electron), effectively making them web apps running in native wrappers powered by Chromium.

9.3.5. Smaller Browser Vendors

Smaller browsers include Samsung Internet, Opera, Vivaldi, Brave, Tor, and many others. Most of these browsers are built as forks of Chromium and rely on the Blink engine. Some, but not all, of these browsers have search deals with either Google or Bing.

These browsers have the ability to add, remove, or modify features in the Blink or Chromium codebase allowing them some significant ability to compete. Despite their small size, it is critical that these browsers be given the opportunity to grow and even now despite their small share they apply competitive pressure on Chrome to meet consumer and developer expectations or be replaced.

However, their ability to steer Blink and Chromium's future relies on these browsers' willingness and ability to invest in the platform’s maintenance and development. Implementing and refining web standards is a costly and complex process, requiring substantial resources. Unfortunately, many smaller browsers have not reinvested enough into Chromium, even proportional to their market share. This leaves the vast majority of the financial and developmental burden for maintaining and advancing Chromium on Google.

For smaller vendors, it is often more difficult to justify investing in the shared platform, work that also benefits their competitors, rather than focusing on features unique to their own browser. By contrast, for companies with larger market share, investing in the underlying web platform is more easily justified. Enhancing the platform increases the overall value of the web, which in turn raises revenue across all browsers. This return on platform investment becomes more favorable the larger the browser share.

However, for the health of the web, it would be far better if the governance and funding of Chromium were more evenly distributed among participants and interested parties.

9.4. Standards Bodies

Web browsers implement designs that are developed and specified in many Standards Development Organisations (“SDOs”) including, but not limited to:

IETF (The Internet Engineering Task Force)

W3C (The World Wide Web Consortium)

WhatWG (Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group)

ECMA (The European Computer Manufacturer’s Association)

FIDO (The FIDO Alliance)

AOM (the Alliance for Open Media)

ISO (The International Organization for Standardization)

IANA (the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority)

Each of these organisations contain a part of the “web standards community”, but feature differing processes, publication gates, and formal mechanisms for including designs into official standards documents. Critically, all of these SDOs create voluntary standards. Companies contribute their intellectual property to the commons of voluntary web standards for complex reasons, but competition has historically driven this process.

In a healthy environment, Web Standards evolve quickly, spurred on by competing browser makers working with developers to solve important problems. This involves collaboration in standards bodies to improve compatibility, however if each vendor had to wait until there was consensus among every vendor regarding every design, it would be possible for a vendor (e.g. Apple) to game these processes. There is also significant risk that well-funded third-parties could infiltrate standards organisations in order to block/stall development or functionality in a manner that is not in the best interests of the user or of competition.

Browser vendors enjoy outsized influence in development of web standards, and providing them with a veto over all progress will only serve to reward the slowest mover by preventing competitors from taking market share. In the existing structure, it is enough for a vendor to withhold engagement and prevent functionality from being standardised. This could lead to a bad situation if there were any rules preventing engines from pushing ahead and using competition to push poor performance with market outcomes.

Typically, cutting edge features are deployed by browser makers in their own engines first, then, using real world feedback over several years, eventual standards are created.

No feature starts out as a web standard:

Web Standards are voluntary. The force that most powerfully compels their adoption is competition, rather than regulation. This is an inherent property of modern browsers. Vendors participate in standards processes not because they need anyone else to tell them what to do, and not because they are somehow subject to the dictates of standards bodies, but rather to learn from developers and find agreement with competitors in a problem space where compatibility returns outsized gains

Alex Russell - Program Manager on Microsoft Edge

No one can predict what web technologies will be important in the future, and disagreements between browser makers on the exact path forward are reasonable and expected. It is very difficult, if not impossible for regulators to predict which standards will be the most important and what their exact definition will end up being. It is a subtle and complex topic, and one that would require significant staffing, over a wide swath of technical areas, for any regulator to credibly participate in.

The existing patchwork of standards groups, along with the social and legal background of voluntary standards, makes recent proposals to bar browsers from implementing features ahead of formal standardisation deeply problematic.

Our analysis of the situation regarding browsers suggests that users and developers do not suffer from too much divergence of views about how to solve leading-edge problems, but rather a lack of engagement and investment in addressing those challenges. We believe this lack of investment stems from reduced competition that browser makers experience on iOS, and to a lesser extent, Android.

The suggestion that individual browser vendors or groups of browser vendors should be able to block all other browsers from producing functionality (that these browsers have no intention of implementing) would further stifle competition.

Requiring consensus before implementation would block the ability of users to signal their discontent by switching browsers to ones that offer the functionality they need. It would also remove any pressure browser vendors might feel to implement popular features if they can block all competitors from providing it. Subtly, it would also reduce the quality of features delivered, because it is only through market-oriented mechanisms like Origin Trials that leading engine teams ensure their designs are fit for purpose.

Apple has held back the Web on iOS (and mobile in general, thanks to network effects) for more than a decade via their veto on features for all browsers on iOS. Handing Apple explicit power to veto features for all browsers would be a disaster. One of the key aims is to break Apple's ability to prevent iOS users from accessing useful web functionality that competes with either their own apps or their App Store.

Browsers (and their engines) need to be free to lead and experiment on the competitive frontier. They need the freedom to be wrong but also to win users through unique features and leading edge capabilities. It is competition, developers and user choice that determines which features will be successful.

Standardization between similar features in browsers is desirable, but it is an outcome that comes at the end of the development and competitive process. It should not be placed as a gate at the beginning. Further, the potential for blocking browsers’ ability to differentiate themselves and compete would be catastrophic to competition.

Our primary concern is not that Apple will have a different vision for how particular features will function, but rather that Apple has already sought to delay features that allow the web to compete with its own, proprietary, Native Apps platform. By trying to ensure that competing features are not available, Apple removes pricing pressure on its native app ecosystem and extends power over developers.

It is important that the excellent work of the W3C and other standards organisations not be weaponized to block innovation and competition, a better approach is regulating to enable effective competition on the gatekeepers operating systems both between rival browsers and between Web Apps and Native Apps. Then allow market forces to push forward the changes (new web features) most beneficial to end users.

Both developers and users gain significant advantages from interoperable implementations of browser functionality. However, it is essential that any interventions ensure that the competitive aspects of browsers are protected including the pressure to significantly invest in new and cutting edge technologies.

Standards should be used to:

Increase interoperability between Browsers.

To allow multiple browser vendors from different companies an ability to be meaningfully involved and provide constructive feedback including but not limited to privacy and security concerns.

Provide implementation documentation for Browser Vendors.

Standards should not be used to:

Reduce or block the level of investment OR remove pressure on vendors to invest.

Reduce or block implementation of cutting edge functionality.

Designate functionality as being exclusive to native (proprietary) apps.

Enable third-parties to undermine features or functionality required by developers or users (i.e. Telecommunication or Advertising Companies attempting to undermine privacy rules).

10. Native App Closed Gardens vs The Open Web

Native app ecosystems are deeply flawed because they place unilateral control in the hands of tech giants, allowing them to dictate the rules, demand exorbitant fees, and centralize decision-making over what can and cannot be shipped. These companies, like Apple and Google, charge developers a 30% cut of revenue from all third-party apps, not because of added value but simply because they control the only avenues for app distribution. Beyond this financial toll, native apps are non-interoperable between operating systems, requiring developers to write and maintain separate versions for each platform. This dramatically increases costs and creates a form of lock-in, as developers invest heavily in specific ecosystems, making it even harder for them to leave or compete independently.

The lack of competition in mobile ecosystems is, at its heart, a structural issue. These companies wield vast power due to the security models on which mobile devices are built. Traditionally, operating systems such as Windows, macOS, and Linux have allowed users to install any application they want, with minimal interference from gatekeepers. Users could grant programs the permissions they needed, offering flexibility and control.

Locking down what applications can do, such as restricting which APIs they can access behind user permissions, is not by itself anti-competitive and can bring legitimate security advantages. However, the manner in which it has been implemented on mobile devices is both self-serving and significantly damages competition.

What is needed is a way to securely run interoperable and capable software across all operating systems. Luckily, such a solution already exists and is not only thriving on open desktop platforms but is dominating, and that dominance is growing every year. The solution is of course, the Web and more specifically Web Apps.

Today, more than 70% of users' time on desktop is done using web technologies, and that looks set to only grow.

These applications thrive on open desktop platforms, and their dominance is growing every year. Web apps run securely within the browser’s sandbox, recognized by even Apple as “orders of magnitude more stringent than the sandbox for native iOS apps”. They are interoperable, requiring no platform-specific adaptations, and do not require developers to sign contracts with operating system gatekeepers. They are capable of incredible things and 90% of the apps on your phone could be written as web apps today.

The web continues to thrive on desktop platforms, where openness and competition enable it to flourish. So why is it struggling on mobile, where just 8% of users’ time is spent in a browser, as noted in the UK’s recent Browsers and Cloud Gaming Provisional Decision?

The simple answer to this question is lack of browser competition on iOS, and active hostility by Apple towards effective Web App support, both by their own mobile browser and by their mobile OS. Apple's own browser faces no competition on iOS, as they have effectively barred the other browsers from competing by prohibiting them from using or modifying their engines, the core part of what allows browser vendors to differentiate in stability, features, security and privacy.

This is referenced in the DOJ vs Apple case where they state:

Developers cannot avoid Apple’s control of app distribution and app creation by making web apps—apps created using standard programming languages for web-based content and available over the internet—as an alternative to native apps. Many iPhone users do not look for or know how to find web apps, causing web apps to constitute only a small fraction of app usage. Apple recognizes that web apps are not a good alternative to native apps for developers. As one Apple executive acknowledged, “[d]evelopers can’t make much money on the web.” Regardless, Apple can still control the functionality of web apps because Apple requires all web browsers on the iPhone to use WebKit, Apple’s browser engine—the key software components that third-party browsers use to display web content. DOJ vs Apple

The DOJ highlighted several ways Apple has suppressed web apps from being a viable replacement to their app store, including bans on third-party browser engines and poor visibility for web apps on iOS. By mandating WebKit for all browsers, Apple ensures it retains unilateral control, blocking competition from engines like Blink and Gecko. This has stifled innovation and entrenched Apple’s dominance.

Fortunately, change is beginning in jurisdictions like the EU, UK, and Japan, where regulators are pushing Apple to relax its restrictions. Mozilla and Google are already working on porting their engines to iOS, and although Apple has erected significant barriers, regulatory pressure is forcing progress. If this trend continues, the web could finally become a competitive alternative to native ecosystems on mobile platforms.

However, this progress is at risk of being undermined by the DOJ's case against Google.

The current funding model for browsers relies heavily on revenue from default search engine deals and this is what incentivises fighting to gain users. While we understand the DOJ's noble intent in canceling such deals, we believe that they have failed to appreciate the depth of the collateral damage that will be done by removing this funding with no viable replacement.

It won’t happen overnight, but stagnation will set in. A stagnated web is incentive for the operating system makers of the world to invest in pulling developers toward those proprietary systems. The browser wars sucked but at least we were still making websites. Being forced to make proprietary apps to reach people is an expensive prospect for the rest of us companies of the world, it will probably be done poorly, and we’ll all suffer for it. Chris Coyer - CSS Tricks

(emphasis added)

This will likely scuttle plans to port both Gecko and Blink to iOS in the EU and eventually in other jurisdictions as Apple is forced to allow competition. Mozilla is going to have a severe hit to their finances, Google will be forced to sell Chrome, and the new owners will be blocked entirely from making a search deal with Google. If the new owners of Chrome are not investing to port it to iOS, a non-trivial investment, this will make it incredibly expensive to port any of the other Chromium browsers, such as Edge, Opera, Vivaldi and Brave.

This will also greatly reduce Apple’s incentive to sustain the recent increase in investment in Safari, which is likely driven by the threat of actual competition in EU, UK, Japan and potential other territories such as Australia.

Any remedy to the current antitrust cases must consider the broader battle between closed ecosystems and the open, interoperable web. History has shown that antitrust actions can inadvertently dismantle one monopoly only to empower another. This outcome is avoidable, but only with careful consideration of the risks to adjacent but interlocked ecosystems.

11. What's in Chromium?

11.1. What is Chromium?

Chromium is an open-source web browser project that powers Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Vivaldi, Brave, and others. Unlike Blink which is a browser engine, Chromium is a full browser making it relatively easy for third-parties to soft-fork and make their own browsers without having to build the full browser shell themselves.

As we discuss below, a vast number of discrete and interconnected technologies are funded under Chromium, some of these technologies are used not only in native apps but are also used in other browsers with their own engines such as Safari and Firefox.

11.2. How is it Funded?

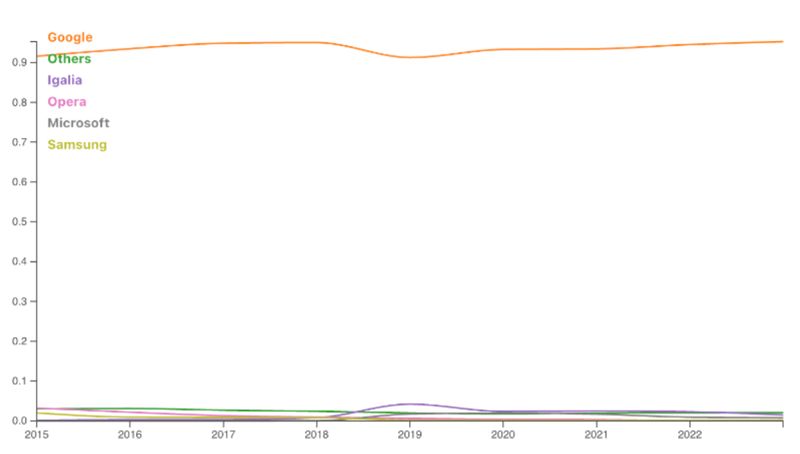

Google recently published a graph showing Chromium’s committed contributions by organization, highlighting a striking statistic: 94% of the project’s commits come from Google.

This raises two perspectives: either Google wields too much influence over web standards, or many companies benefiting from Chromium are failing to contribute their fair share.

Ideally a healthier web would have the investment shared between a greater number of stakeholders, with Google providing sub 50% of the funding in the project. However, the core issue is that many companies have chosen not to fund Chromium adequately, despite the resources they have and the value they gain from Chromium.

The solution is not to cripple Chromium by destroying its primary funding source but to encourage broader investment, ensuring contributors support the project in proportion to their means while having a voice in its governance.

Google, by virtue of having Chrome, invests heavily in the web itself. Not just Chrome-the-browser, but the web standards that power the web. I can’t claim to know every detail of that investment, but I personally know people employed by Google that literally just try to make the web better all day.

And there are evangelists, and documentation writers, and other people who aren’t working directly on Chrome, but really the web itself.

Will Google continue to invest like this if they are forced to sell Chrome? It would be hard to blame them if they did not.

Chris Coyer - CSS Tricks

11.3. What’s in it?

The sheer scope of technologies developed and maintained under the Chromium umbrella is staggering, covering everything from core web rendering and JavaScript execution to advanced networking protocols, security frameworks, media codecs, and developer tools.

This list alone, already expansive, is likely missing additional crucial components that power modern web experiences. Without these technologies, much of the web (and indeed many native apps) simply wouldn’t function at the level users expect today.

11.3.1. Core/Major Chromium Technologies

Blink: Chromium’s Web Rendering Engine.

V8: High-performance JavaScript and WebAssembly engine.

Chromium Embedded Framework (CEF): Framework for embedding web browsers in desktop applications.

Android WebView: Web content rendering component for Android apps.

11.3.2. Graphics, Rendering and Visual

Dawn: Implementation of WebGPU, used in browsers and machine learning tasks.

ANGLE (Almost Native Graphics Layer Engine): Abstraction layer for OpenGL ES on DirectX, Metal, and Vulkan. Used by both Mozilla and Android.

Skia: 2D platform-independent raster graphics library for rendering text, shapes, and images. Skia is used by Mozilla, Chromium, Android and many others.

WebGL2: (Significant Contributor) Open standard for interactive 2D and 3D graphics.

WebGPU: Successor to WebGL, offering lower-level access to GPU resources.

11.3.3. Networking and Communication

Cronet: Cross-platform networking library based on Chromium's networking stack.

WebRTC: Framework for real-time communication like audio, video, and data sharing. Significant collaboration with the IETF and W3C, but the majority of development is driven by Google's engineering teams. LibRTC, derived from WebRTC, is extensively used in native applications.

QUIC/HTTP3: Faster, secure transport protocol replacing TCP in many cases.

SPDY/HTTP2: Earlier work to optimize HTTP communication

Brotli: Advanced compression algorithm for web content.

Certificate Transparency - Chromium has driven the adoption of Certificate Transparency, a framework for logging all issued certificates in public, verifiable logs.

11.3.4. Developer Tools and Debugging

Chrome DevTools: The most widely used and essential suite of tools for web developers, enabling efficient debugging, profiling, and optimization of web applications. It is the primary choice for most developers developing on the web platform, providing unparalleled capabilities to inspect, edit, and debug HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and network performance in real time. Chrome DevTools is used within every Chromium-based browser.

Lighthouse: Automated tool for improving the quality of web pages (performance, accessibility and SEO).